On Jan. 31, the Supreme Court agreed to consolidate and hear two cases filed by Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina, regarding the lawfulness of race-conscious admissions, widely known as affirmative action. The court’s decision on both the Harvard and UNC cases will be crucial in determining the future of affirmative action in college admissions.

Ending race-conscious admissions will have disastrous effects on the acceptance rates of racial minorities — especially Black, Indigenous and Latinx students. Given that inequities in education are complex and deep-rooted, the lack of upward mobility for minority students must be addressed in the short term through race-conscious admissions. Affirmative action is far from perfect, but it is simply meant to be a reactionary measure to reduce the ongoing harm against students of color.

The Supreme Court’s 2003 decision in Grutter v. Bollinger maintained that the use of race as a factor among qualified applicants was constitutional, and was an important step toward racial integration and the compelling need for diversity on a college campus.

It is highly unlikely that the court will maintain this decision. Six of the nine justices are conservative and multiple have openly opposed affirmative action: Chief Justice John Roberts has long been a staunch opponent, declaring in a 2006 opinion, “It is a sordid business, this divvying us up by race.”

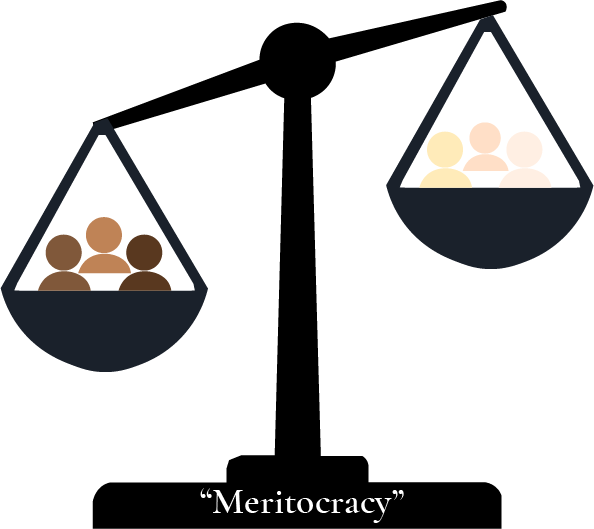

Opponents of race-conscious admissions like billionaire conservative Peter Thiel often argue that the policies erode the purity of a meritocracy — after all, the privilege of admission to the nation’s most prestigious institutions should depend on individual achievement as the sole criterion of merit.

This would be undisputed if we actually lived in a meritocracy where these factors equalized rather than exacerbated the disparities between the privileged and the marginalized.

Unfortunately, we live in a society where marginalized students of color are disproportionately enrolled in schools with poorer curriculum quality, significantly less funding than their majority white counterparts, less skilled teachers, not enough books, computers or laboratory equipment, minimal funding for extracurricular activities and reduced or no access to college preparatory resources.

Combined with the higher rates of poverty, violence and undiagnosed mental and physical health issues marginalized students face outside the classroom, it is impossible to fairly compare the admissions profile of a white suburban student from a well-resourced school with that of an impoverished Black student from an under-resourced school without taking into account the circumstances of each student. These disparities are almost inextricably linked to race as a result of centuries of deep-rooted racial oppression.

If affirmative action opponents truly cared about ending unfair advantages, they would have already tackled the issue of legacy admissions — the practice of prioritizing applicants with alumni parents or family — rather than disproportionately focusing on programs that help minority students. Compared to Harvard University’s overall acceptance rate of about 6% from 2014 to 2019, applicants with legacy status enjoyed a 33% acceptance rate.

Most legacy students are white and wealthy: For the Harvard class of 2021, 46% of legacy students reported family income upwards of $500,000, while almost 70% of legacy applicants were white. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research estimated that roughly three quarters of legacy students would have been rejected if their applications had been treated the same as white non-legacies. Despite this striking disparity, there is sometimes radio silence when it comes to the issue of unfair legacy admissions.

In the past, Students for Fair Admissions has expressed their stance against legacy admissions. However, given their vast resources, their inaction on this front compared to the fervent legal pursuit of race-based affirmative action demonstrates where their priorities truly lie.

It is important to critically examine the basis of the outrage against affirmative action — when marginalized groups are blamed for “taking the places” of white and Asian students, it conveys an unspoken sense of entitlement, an “us versus them” mentality, as if students who benefit from affirmative action are less deserving of admission.

That’s not to say that race-conscious admissions are a perfect process. Although meant for racial minorities, white women have been some of the largest benefactors of affirmative action, especially in the workforce. Additionally, it can sometimes benefit affluent minorities more than working-class or impoverished ones.

The solution to these problems does not lie in abolishing race-conscious admissions. As long as steep racial disparities exist in the U.S., “blind” college admissions will continue to disproportionately favor wealthy and white applicants. Instead, working to reform affirmative action policies to further consider socioeconomic status, first-generation or immigrant status, will ensure that the policies can help those who truly need it.

Affirmative action is a band-aid, temporarily covering the gaping wound caused by long-term socioeconomic and racial inequities in America’s education system. The Supreme Court must uphold it to protect minority students who are denied the opportunities that wealthy, white students are handed. American society is not, and has never been, a true meritocracy for poor students of color. It is time to acknowledge that.