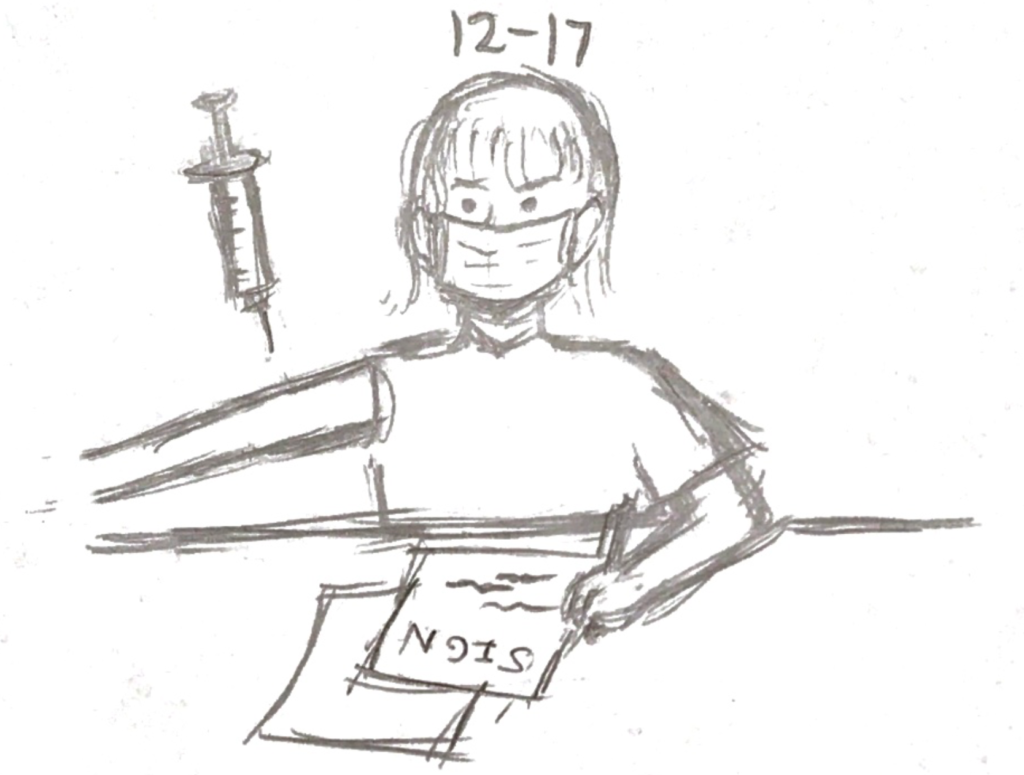

The school hosted a COVID-19 Vaccination and Booster Clinic on Jan. 22, providing opportunities for students and the community to strengthen their immunization against the omicron variant. As teenagers waited in line, they were escorted by parents who signed papers of consent, as the vaccination process for teenagers ages 12-17 requires legal approval from parents or guardians.

However, two days prior, amid a wave of new bills proposed during California’s legislative session, San Francisco state senator Scott Wiener introduced Senate Bill 866: A proposal which would permit minors between 12 and 17 to get vaccinated without parental consent. If passed, the bill would cover any FDA approved vaccines that meet CDC immunization recommendations — notably, the COVID-19 vaccine, as well as shots for flu, measles and chickenpox. It would go into effect on Jan. 1, 2023.

In areas such as Santa Clara County, the bill may not have a drastic impact. COVID-19 vaccination percentages for teens in the county are significantly higher than statewide statistics: As of March 29, among eligible 12-17 year olds, 80.2% are fully vaccinated, compared with California’s 65.8%.

Nevertheless, teen vaccination rates continue to lag behind adult vaccination rates, with 95.1% of adults in the county ages 18-49 fully vaccinated and 77.3% in the same age group in California. According to Wiener, the new bill would empower teenagers to make their own health decisions and improve vaccination rates overall.

Local opinions on Senate Bill 866 are split. While some praised the bill for giving teenagers the ability to protect themselves against disease, others brought up concerns about the bill blocking parent involvement and responsibility in their children’s medical decisions.

History teacher Mike Davey is one of those with mixed feelings about the bill. On one hand, he strongly believes in the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine and respects lawmakers’ efforts in getting more teenagers vaccinated — especially due to the high number of close contacts high school students have from switching classrooms throughout the day. However, he is hesitant over letting children as young as 12 make medical decisions on their own.

“It’s certainly a gray area,” Davey said. “I would generally say that I would support anything to encourage people to get vaccinated. But this might not be [something I can support] because it takes it out of the parents’ hands.”

Davey also cited the wide range of ages included in the law as another factor to take into account.

According to the Associated Press, different regions of the country have varying vaccine minimum consenting age laws, the lowest of which is Alabama allowing 14 year olds to consent, followed by Oregon at age 15. If the bill is passed, California would have the youngest consenting age.

Davey believes that pre-teens near the bottom of the bill’s targeted age group are in a completely different situation from high school seniors bordering adulthood.

“I don’t think you can make a blanket statement,” Davey said. “The reason that 12- and 17-year-olds are included in the bill is because that group got vaccinated together, but I think there’s a big difference when you’re talking about a kid of age 12 versus someone of age 17.”

On the other hand, freshman Will Norwood said he thinks Senate Bill 866 is worth supporting because increasing vaccination rates will help stop the spread of the virus. Although he finds that the topic is controversial due to health care being traditionally controlled by parents, he believes that “it’s important to allow kids to make the right choice about vaccines.”

Additionally, he feels it is important to discuss the repercussions from parents at home if a child gets vaccinated without their consent, he said. He finds the culture in Saratoga to be one where parents like to take charge and control a child’s life — whether for academics or medical decisions on vaccination.

“I’m very grateful that I have parents who agree with me, align with my political views and agree that vaccines are safe and scientifically proven,” he said. “But I sympathize with people who want to get a vaccine but can’t get access to it if their parents don’t necessarily agree with them.”

The prospects for the bill to pass into law remain remote, observers say, due to vocal opposition. Norwood thinks this is because politically active anti-vax parent groups will have the power to push back the bill. Although they comprise only a small percentage of the general population, they are overly represented in California’s legislature, he said.

Nevertheless, Norwood and Davey are hopeful that COVID-19 vaccinations will be required for anyone attending schools in person next fall. They believe that it should be the standard, given that California already has vaccine mandates for diseases — such as polio, tetanus, measles, mumps and rubella — in place to protect students and staff.

On Jan. 24, just a few days after Senate Bill 866 was put forth, senator Richard Pan proposed Senate Bill 871, which would close loopholes in mandating the COVID-19 vaccine for California schools. Although Newsom already approved a vaccine mandate for both public and private in-person schools upon the FDA’s full approval of the vaccine for respective age groups, the previous mandate allowed exemptions for personal and religious beliefs; however, Senate Bill 871 would only allow exceptions for medical reasons.

Both bills have yet to pass through the California Senate. As of March 29, Senate Bill 866 is pending approval from the Senate Judiciary Committee.

“I think it will be very interesting to see how it plays out,” Norwood said. “I’m excited to see what will actually change if this bill does pass, and even if it doesn’t, it will still affect the way we perceive vaccines for minors.”