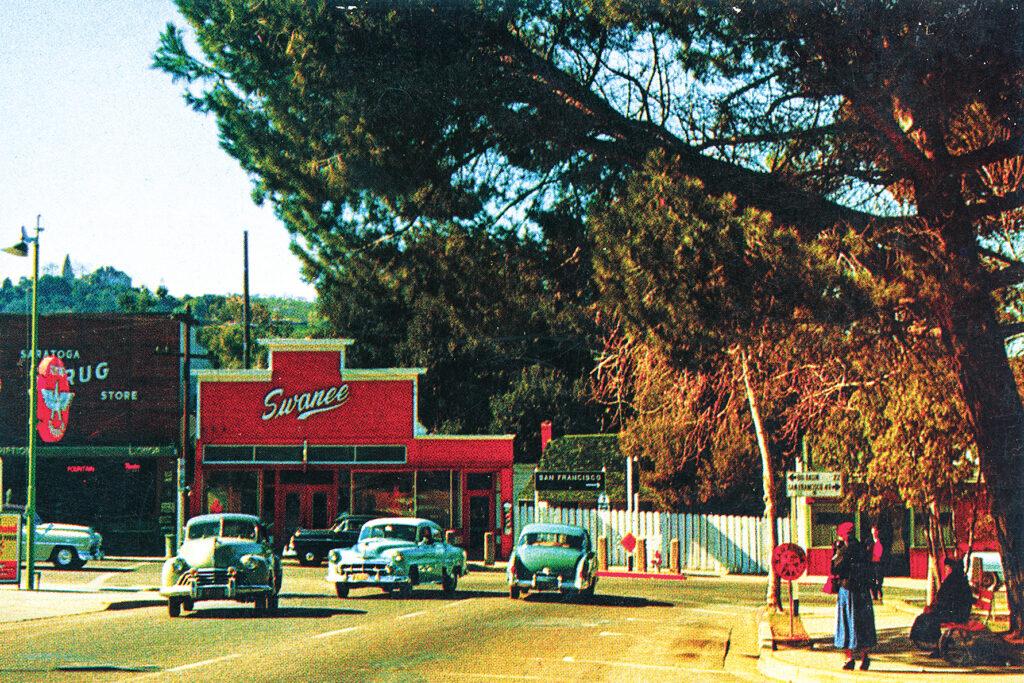

In 1968, Mary Monroe was a senior at the school and was the ASB treasurer. She lived in a secluded house on top of a hill surrounded by orchards on Glen Una Drive. Her high school sweetheart and later husband, Kim Monroe, the Class of 1968 ASB president, frequently biked through streets that were then still lined with orchards rather than multimillion-dollar houses on his way to school.

Then, the school’s 1,461 students were mainly from white, upper middle class families living in booming suburbs of a growing tech industry. Other students came from farming families who tended to vineyards and horses.

In the 54 years since the couple graduated, many of those family farms have disappeared, transforming the then-agricultural environment to the pricey upper class neighborhoods of today. This change in scenery and socioeconomic status of students is just one of several staggering changes in the school highlighted by the school’s 1968 Western Association of Schools and Colleges’ (WASC) record, a 246-page documentation of the school’s climate, courses, academic statistics and concerns.

Since WASC’s founding in 1962, the organization has asked schools to self-study their culture and campuses and, in return, earn accreditation that verified them as providing adequate educations. WASC is responsible for accrediting the schools in California, Hawaii, Guam, American Samoa, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Palau and Northern Marianas Islands. If a school isn’t accredited, state colleges and universities will not accept its student applications.

In the WASC accreditation process, schools use rubrics to self-study and rate attributes such as school services, personnel, student culture and academics.

During evaluation years, the school, led by a WASC coordinator as a school staff volunteer, prepares a binder full of information collected over the year. The procedure involves several committee meetings where administrators, teachers and select students discuss and evaluate individual reports, which are then summarized into a list of major recommendations. Faculty and administrators then use these recommendations to improve the school.

For example, in response to a 1968 WASC recommendation that the school should continually evaluate how effectively it is achieving its objectives, faculty conducted evaluation studies of graduates’ records, collected reports on first and second-semester grades from colleges and set up informal personal conferences with graduates and their parents.

After reading and evaluating the report and visiting the school, WASC gives a term of accreditation anywhere from one to six years based on how well the school meets their criteria.

“Saratoga has always gotten a six-year [accreditation term] because they’re not too worried about the school in terms of meeting the needs of the students,” said now-retired assistant principal Kerry Mohnike.

From outdated language to yellowed pages, the 1968 WASC record on Saratoga High comprehensively describes a seemingly foreign school culture, course selection and system of assessing and placing students in classes.

While there were some similarities between the school in 1968 and now, including low dropout rates and top academics, nearly everything else has changed.

IQ Tests: standardized exams of the past

While state-mandated standardized tests like the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP) are currently used to gauge student academic performance and construct a school’s profile, a different and controversial test was used then.

In 1968, incoming freshmen and transfer students were administered the Lorge Thorndike test, later renamed the Cognitive Abilities Test, which estimated students’ problem solving abilities through verbal, nonverbal and quantitative tasks. The California Achievement Test (CAT) measured reading and mathematics levels.

Intelligence Quotient (IQ) tests measuring students’ innate abilities, which were selectively administered to graduating classes, were then separated into two sections: students with an IQ of 115 or above, and the rest of the class. The school then analyzed the percentages of these “upper students” who completed an adequate number of courses in English, math, science, foreign language and social studies.

A teacher who saw the downside of using these tests was Dr. Hugh Roberts, one of the school’s original social studies teachers who was hired when the school opened in 1959.

“When I was teaching, counselors would use or misuse IQ tests as one of the measures to suggest future employment or college,” Roberts said. “They used them less and less over time.”

In the 1960s, enrollment in advanced classes was contingent on achieving a certain score on standardized tests. For example, some classes would administer the reading exam to determine whether a student would qualify for it.

According to Roberts, the school didn’t strictly uphold such policies of test-in classes. Admission into more selective courses was primarily based on past teacher recommendations, and students would be given a pretest about material later covered in the course.

“I don’t believe I ever refused a student who showed up for a class,” Roberts said. “After the pretest and the first set of assignments, if the student’s performance was so low that they would do badly later on, I would counsel them to see if they still wanted to try it. If they did, it was their choice.”

Unhealthy academic standards since 1968

Even in 1968, the WASC documentation shows that parents had “unrealistically high” aspirational goals for children — but while expectations were generally similar for male and female students, the reasoning differed.

While college education was viewed as a “necessity for the economic success of the boys,” girls were expected to have “sufficient” college experience to prepare for a good marriage, an opinion deemed as “important” by 90% of parents of incoming freshmen, according to WASC records.

In 1965, 133 students — 86% of the graduating class — planned to attend college, 23% of which went to state universities. 20% attended state colleges, 19% attended other four-year colleges and 38% attended two-year colleges, with 94% of those students attending West Valley.

Mohnike, who started working at Saratoga High in 1991, believes the school has always been academically focused.

She does believe, however, that student stress levels have grown since the 1990s, since the competitive nature of the college application process has intensified.

A study by the American Psychological Association (APA) stated that students in the 1980s reported more anxiety than child psychiatric patients in the 1950s.

“When I was in high school, almost anybody that had a decent GPA could get into UCLA,” Mohnike said. “Now it’s very difficult for students to get into colleges like UC Berkeley and UCLA. It’s just that the pressure on the seats has gotten worse.”

A look into past course offerings

The 1968 WASC report showed that classes were markedly different from today. More humanities-focused courses were offered: visual and performing art, sociology, homemaking, music and industrial art. In some homemaking classes, the school taught sociological aspects of family problems. Other offerings included office practice, typing, salesmanship, woodshop and autoshop.

Homemaking, a group of electives taught from 1959 to 1981, sought to “integrate and apply [all the subjects taught in high school] in the daily process of making a home,” the report said. Such classes were primarily taken by girls.

Also known as Home Economics, the course involved helping students develop the “appreciation, knowledge and skills necessary” for effective participation in home activities: Specifically, the curriculum consisted of four two-semester courses, teaching subjects from foods, clothing and furnishing to courtship, marriage and family, which prepared girls for marriage.

According to the 1968 WASC records, the average Home Ec student “[came] from a lovely home with progressive parents. They want[ed] help in planning, entertainment and decorating for gracious living.”

The course was marketed toward the “less able student” who was usually “discouraged” by the prerequisite of biology, chemistry, mathematics and other STEM classes to apply for college. It stressed the importance of budgeting, using credit wisely and other consumer buying practices to aid students’ “expensive tastes for gourmet foods, social graces, flower arrangements and history of furniture and architecture.”

Members from professional departments were invited to the school to provide their perspective in homemaking departments. Doctors, parents, nursery school directors, pre-school children and returning SHS alumni were invited to provide different outlooks and ideas for the students. In the food sector of Homemaking I and II, for instance, the school invited butchers to present lessons on meat.

The curriculum for these classes were created solely by teachers and advised by alumni, institutes and professional publications, as there were no textbooks or state guidelines to follow.

The content taught in other humanities classes has also changed drastically. While World History and U.S. History were still required, the school also mandated civics and sociology for most students while offering Asian History, Latin American History and World Affairs as electives.

The civics class involved students assisting city and state elections by having them campaign to get higher voter turnout. It also focused on evaluating and understanding ballot measures as well as the results of elections.

Similar to how there are currently various levels of the same subject (e.g. regular, honors, AP), some of the social studies classes used to also be separated into ”lower level classes” for “less able students,” and “higher level classes” for “regular students.”

Other electives, such as drafting, typing, shorthand, book-keeping, salesmanship, office machines operation and office operations, were created on the basis of giving “terminal students certain skills that will have market value.”

Students taking office-related classes were given on-the-job instruction in the school’s office, while other students were provided opportunities in custodial and gardening work.

Another major difference in courses is that students who were deemed “less proficient” through standardized tests were tracked into less challenging classes.

There was an A track for students considered to be likely-college-bound, a B track for students in the middle of the road and a C track for students considered to be “less smart.” Students in the lower tracks received less work and learned less than the higher tracks.

“Tracking is kind of antiquated and people now understand that’s just not the best way to help people to grow as students,” Mohnike said.

Roberts said many teachers fought against tracking because it often caused students to live up or down to their label.

“I was really bothered by having a tracking system at Saratoga High School — it was so intellectually indefensible,” Roberts said. “There was a rebellion among the staff and the administration to get rid of those programs.”

The movement against tracking started as early as the second year of the school in 1960, Roberts said, and the practice eventually ended in the 1970s. Afterwards, teachers were encouraged to offer more electives to provide more academically rigorous opportunities. The Advanced Placement (AP) classes were introduced to the school in 1984.

School spirit in the ‘60s

School culture was dramatically different in the 1960s. The married couple, Class of 1968 ASB President Kim and ASB Treasurer Mary Monroe, believe students had much more free time to explore different interests.

For his part, Kim participated in rock ‘n’ roll bands since middle school, swam competitively for a few years of high school and was part of the football team in his senior year. When he and other candidates were campaigning for school government, they put on skits or other activities in the quad.

Though student activities were more organic, restrictions on student behavior in the 1960s were significantly stricter. Kim recalls how the Dean of Boys — assistant principals who supervised different groups of students based on gender — had refused to let one student graduate with a mustache. A similar instance happened to another male student with very long hair.

Mary also remembers how she and Kim were told not to hold hands when they were walking down the hallway. The Dean of Girls did not allow female students to wear pants to school and required that their dresses be a certain length. There were also separate P.E. classes for girls and boys. The school’s rules generally reflected the opinions of parents in the community.

However, parents and students alike “fought like crazy” when “New Math,” a learning crusade that stressed conceptual understanding of mathematical concepts over technical computing skills, was introduced to the nation in the 1960s.

While getting into a top college is one common goal for the student body now, Kim said students in the 1960s weren’t particularly focused on college admissions. Mary was even advised not to go to college. Even so, both chose to attend college and graduated from UC Santa Barbara in 1972.

Demographics and student activism

Most classes in the 1960s and early 1970s weren’t equipped with textbooks. In cases such as the sociology course taught by Roberts, who taught at the school from its opening in 1959 to 1979 and served as the former head of the Social Studies Department, freedom in curriculum structure gave students more opportunities to interact with the community.

“After the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978, the necessary information taught in classes became heavily structured with less creativity and very little involvement of the students,” Roberts said. “Before then, I always had students doing social experiments. I had them out in the community conducting projects and sharing their results with the class.” Proposition 13, still controversial today, puts a cap on property taxes paid by homeowners and businesses. It was a devastating financial blow to all public K-12 schools, but advocates argued it was needed to allow elderly homeowners to stay in their homes and not be forced out by huge property tax bills that grew as prices increased.

Two students from the Class of 1968, Jamie De’Angelo and Kim, were inspired by Roberts, who was then working with the American Sociological Association on a National Science Foundation grant and writing paperback books on topics such as poverty and racism in America.

1968 was a year rife with political upheaval and civic action, from the Vietnam War to the height of the Civil Rights movement. During this time, many schools on the East Coast held “incredibly active” Black student unions, Roberts said. He and other faculty members also took a day off from work to join an anti-Vietnam War protest in San Francisco.

Interestingly, the school rarely had more than two African American students at a time. In 1968, approximately 97% of the school’s student population was Caucasian; of the 1,461 students enrolled, only six were “East Asian” — a far cry from the 60% of Asian American students who now attend the school. WASC records describe the then-minority demographics enjoying the “same socio-economic status as those of the rest of the community,” with the exception of a dozen Mexican-American students from farm-labor families.

“Students here felt they had no prejudice,” Roberts said. “They didn’t even know anyone who was Black.”

In an attempt to educate students about racial diversity and to promote active change against racism and override stereotypes, Kim Monroe led student exchanges by bus that year with Overfelt High School’s Black student union in East Side San Jose.

“We thought, well, here we are in lily-white Saratoga and we don’t have much connection with other people from different backgrounds,” Monroe said.

There are mixed accounts of the exchange between Monroe and Roberts: Roberts said that three busloads of students from each school traveled to the other school, whereas Monroe said Overfelt High students visited Saratoga once, and Saratoga High students never went to Overfelt High.

Nevertheless, students discussed issues pertaining to race in all classes — foreign language, science and mathematics, for example. The day ended with a small party and dance.

De’Angelo, another student from the Class of 1968, led a petition of students to change the dress code, which prohibited girls from wearing pants and skirts above knee-length. The petition proved successful in 1970.

Roberts and his sociology students also investigated discrimination within the community, a practice called redlining. For example, from the 1930s to the 1960s, developers used covenants and other means to to keep Blacks and other minorities from buying homes in some majority-white neighborhoods — in fact, one of Monroe’s neighbors threatened to bomb his house if his family sold it to a Black family.

In response to this kind of gross discrimation, Roberts created a petition in support of a Black couple moving into Saratoga. An “overwhelming percentage” of Saratoga residents signed.

Students in his 1968 sociology class researched the stereotypes about Black people and other minorities, and broke them down into survey questions to gauge student attitudes on a 1 to 6 scale.

“The results tell you that the degree of strong prejudice in Saratoga has never been that high,” Roberts said. “It’s been talked about a lot, but it’s been mild relative to the total culture in the United States.”

The two-page survey, frayed, folded and ripped at the edges, still holds characteristics representative of documents at the time — monospace font on typewriters and ink that bled through. The 1968 WASC records — filled with aphoristic quotes from the faculty committee, administrators’ suggestions, observations and reflections regarding the school’s philosophy — show how much has changed in the more than five decades since.