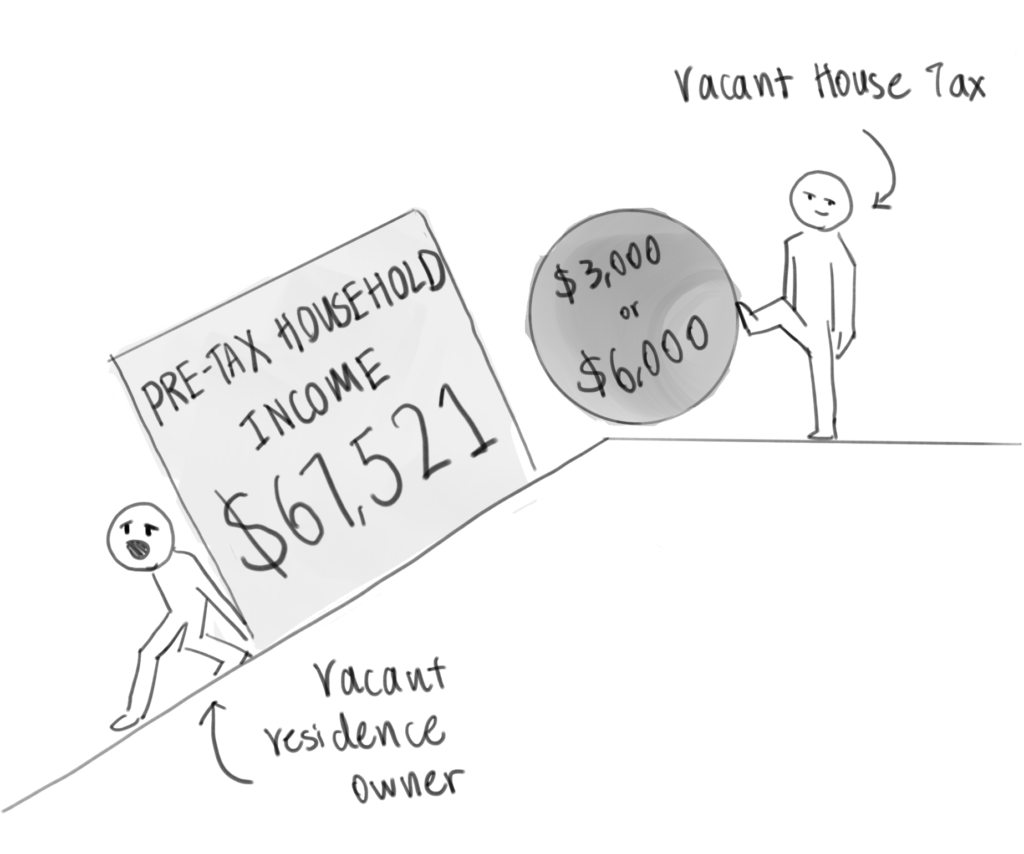

Already needing to pay a median pre-tax household income of around $67,521, most homeowners in the U.S. are likely not excited to kiss goodbye to an additional $3,000 or $6,000 in taxes yearly (4.4% or 8.9% of annual income on median) from their bank accounts for each vacant residence they own.

A traditional rule of thumb is that roughly 30% of a person’s income should be spent on housing, according to CNBC. Spending an additional few thousand dollars on vacant residency taxes would likely create a large dent in the average household’s budgeting plans.

However, the widely suggested vacancy tax proposals (also known as the Empty Home Tax in Santa Cruz) are becoming more popular across the country in cities such as Santa Cruz, Washington, DC, San Francisco and Los Angeles. If these policies are implemented, tax rates of $6,000 per single-family residence, $6,000 per residential parcel with six or fewer units and $3,000 per residential unit of a condominium or townhouse would be implemented for homes that are vacant for 120 days.

In Santa Cruz, 72% of residents are renters (not homeowners) and pay expensive Bay Area prices for a scare commodity. Roughly 8% (24,029) of units are reported vacant.

These percentages are the norm across the country, where the average homeowner in the U.S. is 40 times wealthier than the average renter.

However, these proposals completely ignore many housing and familial situations, and the exemption list for the tax is far too short. Current exemptions include loss of job, hospitalization, long-term care, active legal proceedings and construction.

However, there are plenty of other valid excuses a homeowner could have that should qualify them for an exemption, the first and most obvious being that not all homeowners are rich. Proposal writers and supporters are simply making the assumption that all homeowners with a vacant residence are “rich”; however, not all second properties are vacation homes, and most people who own multiple properties are not millionaires.

In the U.S., fewer than 64.8% of people own a home, and according to NAHB, 5.5% of the total housing stock were second homes in 2018, totaling 8.5% of homeowners owning two or more properties. I think it’s safe to say that not everyone in this 8.5% is a rich capitalist who has enough pocket change to purchase a new car. In fact, in 2006, second homeowners had a median annual household income of $80,600.

Given that having a second home doesn’t equate to being filthy rich, there are dozens of reasonable causes for a vacant property. Owners could be having trouble finding renters during a down housing market, an estate transfer or probate could be delayed, landlords may be using buy-to-leave strategies on an investment home, property owners could be living in a different state or even country on business and planning to return in the future, or the property could be in poor, unlivable condition but the owner may not have the financial means to repair the property.

In addition, even if some people may be looking to rent out their homes, they may not be able to. Many vacancy proposals are ignorant of how many condos, apartments and gated communities are controlled by an HOA (HomeOwner’s Association), which enforces rules, maintains facilities and often enforces rental restrictions.

In the proposed Santa Cruz vacancy tax, homeowners will be given 120 days to occupy their property. However, when rental restrictions are enforced, there is a cap set by the HOA on the percentage of homes allowed to be rented out in the community. If the set cap is met, homeowners looking to rent out their properties are restricted in their ability to rent their property and are often placed on a waitlist, which can take months or even years to resolve.

So where do these vacancy taxes leave these homeowners? These homeowners want renters to occupy their properties, but they are most likely legally unable to do so within 120 days.

Other than collecting vacancy taxes, vacancy proposals also “encourage” owners to rent out their homes, which, in theory, provides more housing on the market.

However, proposals incentivizing people to rent out their homes do not solve the housing crisis in many large cities, mainly due to vague or a lack of rent control laws in many areas. Though there are rent control and eviction laws in place in many states, including California, being a landlord is a difficult task that involves many legal burdens, and is a job that homeowners should not need to take up by the government.

In a bad market, many real estate investors, who are, in essence, professional landlords, find themselves underwater or barely breaking even on their rented-out investment properties. Creating a situation where vacant homeowners, who cannot afford to spend a large amount of their paycheck on an additional tax, are forced to either sell their properties or deal with the hassle and burden of managing renters is unethical and ignorant — and may ultimately backfire on policymakers by resulting in less housing.

Landlords who are having trouble finding renters would be encouraged to sell their properties to avoid the vacancy tax, and though a small percentage of vacant homeowners may choose to rent out their homes, as the policy suggests, nothing is ensuring that they will rent at a fair price. So yes, there may be a few more properties on the market, but not necessarily more affordable properties.

No matter how rich or poor a homeowner may be, it doesn’t justify the government essentially pressuring people into renting their homes out by incentivizing them with the idea of avoiding an expensive tax. Even if a billionaire owns dozens of properties consisting of an assortment of beach houses, lake houses and ski chalets, it’s definitely not anyone’s business to be tracking what they are doing with their properties.

The only thing a vacancy tax succeeds in is deterring prospective home buyers from purchasing in a certain area and encouraging current homeowners to sell their properties and purchase elsewhere, leading the government to not only lose out on their vacancy tax but their property tax as well.

If the government were to decide a vacancy tax was absolutely necessary for a certain area, they should at least think the plan out clearly — there are plenty of other avenues to pursue to fund affordable housing.

If policymakers decide that a vacancy tax was unavoidable, before imposing a tax on a homeowner, the government should verify that the homeowner has the financial means to pay the tax. They should also verify that the home is a luxury or vacation property that is nonessential and that the tax percentage is reasonably proportional to both the home owner’s net worth and the vacant property value. It would be unreasonable to tax the owner of a vacant property valued at $10 million the same amount as the owner of a home valued at $80,000. Stop imposing ridiculous taxes that are targeted toward the wrong group of people in an effort to avoid coming up with reasonable solutions for affordable housing.