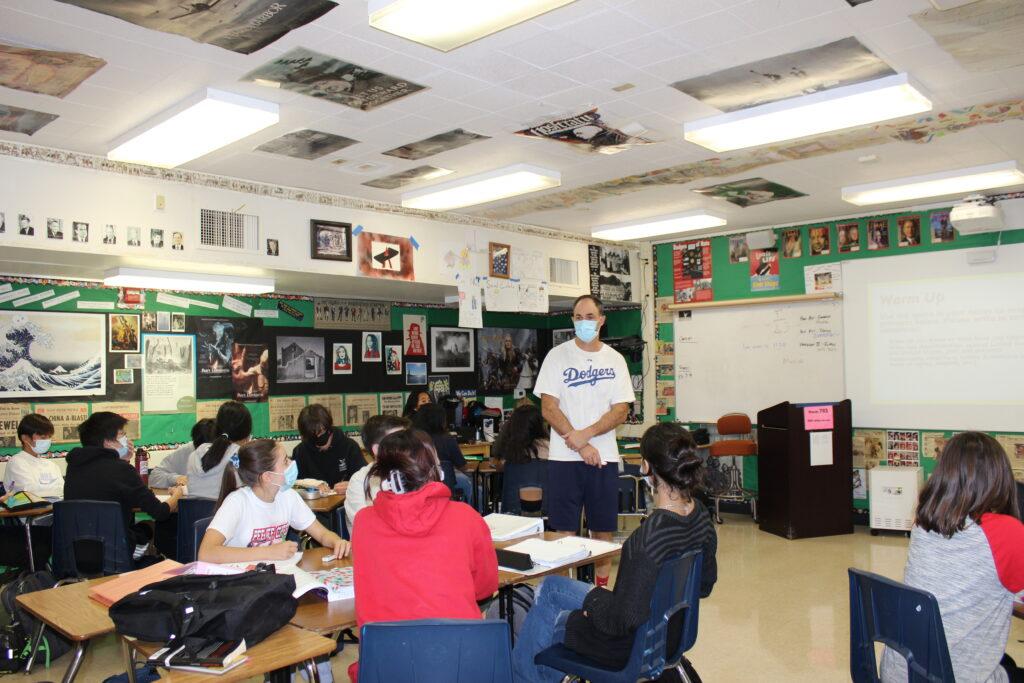

An NPR news broadcast featuring current events played when freshman Aakanksh Gurnani walked into room 703 for 5th-period Ethnic Studies on Sep. 24. When the bell rang for the start of fifth period, social studies teacher Mike Davey enthusiastically greeted the students and then launched into the fast-paced lesson on the recent history of Afghanistan.

In early 2021, California began working through a highly contentious bill requiring an ethnic studies course for high school graduation. Newsom signed this bill into law earlier this month, making California the first to mandate an ethnic studies course for a high school diploma.

The bill states that public high schools in California are required to offer an ethnic studies course starting in 2025, although high school students will not be required to take the course to graduate until 2029.

Schools will have the freedom to plan the curriculum under Assembly Bill 101, which allows schools to develop their own format for courses if approved by the local school board subject to public hearings. Prior to Newsom’s approval of the mandate, previous state legislators have proposed similar bills and been rejected.

This year, freshmen were given a choice between a semester of either ethnic studies or world geography to take along with the one-semester health and driver’s education class.

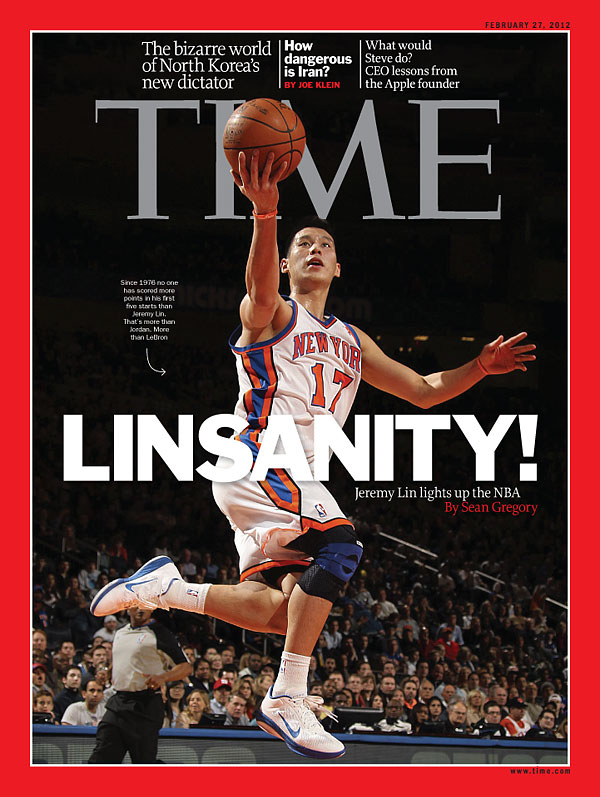

The course, created by Davey, focuses on perspectives of minority groups, as many current social studies classes mostly concentrate on European history with a Eurocentric point of view. The major units explore Native Americans, Black Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans and LGBTQ+ history.

“The class explores a lot of history that is often not taught or is normally glossed over,” Davey said.

The class focuses on these marginalized groups’ experiences and their fight for rights in current-day society, Davey said. The course ends with students choosing an issue that they’re passionate about and creating a social impact project, which revolves around that topic.

“They have to pick a topic that speaks to them,” Davey said. “Throughout the year, we’ve heard about some of the problems that different groups have faced in American history. Now, their job is to find a solution. Either identifying the problem, taking a stand for certain groups or something to that effect. It’s really open ended, they get to choose what they’re going to do, and then they have to present it to me to make sure it’s constructive.”

The course generated controversy last spring and summer when a group of Los Gatos High parents claimed that it teaches Critical Race Theory — an academic movement of civil rights activists who seek to examine the relation of race and the law as well as focus on racial justice — which, in their opinion, elicits low self-esteem from white students, as well as teaches Marxist ideology to students. They are upset at the proposal by the school board for this course to be offered at LGHS, arguing that the nature of the class is racist. Currently, the class is not being offered at LGHS, although due to the new bill, the class will have to be offered there no later than the Class of 2030.

However, at SHS, ethnic studies and its curriculum have seemed to be well received by the students. Gurnani believes that the class is a fresh take on history because it is unlike any course he has taken in the past due to its emphasis on the points of views from minorities.

“I think the most valuable thing I’ve learned so far was the idea that history is not defined by the actions or one-dimensional story from a single party, but rather should be looked at from all of those affected,” Gurnani said. “Most classes mainly focused on the dominant narrative, which is usually white people.”

Through learning about various minority groups, he is looking forward to being able to further understand and analyze key events in American history from all perspectives.

These events are not just limited to the past, however. Due to the class’s emphasis on current events, the students are able to connect historical events to today’s social issues, such as COVID-19 cases and how it is correlated with the rising xenophobia in the U.S. as well as what the government is doing in response to global events. Despite the novelty of the class, the majority of freshmen still opted for world geography. Freshman Eunice Ching said she didn’t take ethnic studies because she wasn’t well informed about the class in general.

“I didn’t even know what ethnic studies was, so I just chose world geography,” she said. “Although I now know about it, my friend in that class [said that she] receives more work than I do in world geography, so I’m not sure I would switch into that class even now.”

Freshman Lucy Le Toquin agrees that there is a lot more coursework associated with the ethnic studies course, which she is taking this semester. She said that this class is much faster paced than her other classes; however, Le Toquin believes that the increased coursework has a payoff.

“I’ve learned so many things that I didn’t know before and that I can use in the future,” she said. “I feel like if something ever happens in the future, we would have more knowledge about it or if someone makes a joke that’s not OK I can tell them ‘Hey, that’s not OK.’ Because of what we learned in Ethnic Studies, I can use my knowledge for good, and speak up if I see something that’s not fair.”