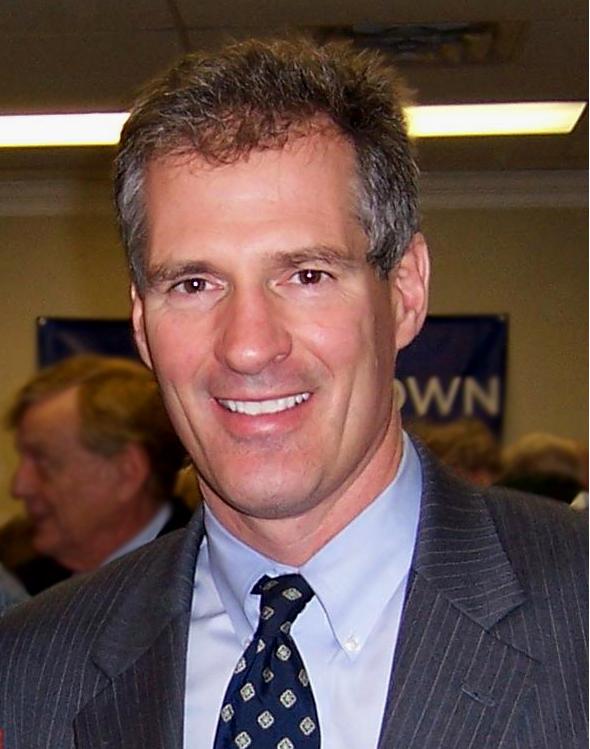

“We can do better!” Massachusetts Senator-elect Scott Brown (R-Wentham) declared to an audience of supporters following his landmark victory. As much as disgruntled Democrats would like to believe he was referring to his election, Brown was instead alluding to the lack of tangible change made on Capitol Hill in the year since President Obama was sworn in.

In apparent rejection of this lack of progress and fear over progress itself, Massachusians voted overwhelmingly in favor of Brown to assume the now-vacant Senate seat that the late Ted Kennedy, a liberal Democrat, had held for more than 40 years—effectively toppling the Democrats’ filibuster-proof majority, balancing the political landscape, and putting an indefinite standby on the already prolonged debates over health care, Gitmo, and Afghanistan.

But if Americans think that electing Brown will be their political saving grace, they are wrong. Leveling the political playing field has its merits, but expedited and more productive legislating is not one of them.

Previously, the lack of real progress could be attributed almost solely to conflict within the Democratic Party. Even considering the health-care debate singularly, Democrats were critically divided over whether or not to implement the public option. Though they had an effectively omnipotent majority, inconsistent views within the party itself prevented any bill from ever reaching Obama.

Following Brown’s taking office, the Democrats will have another new league of problems. Not only will a prospective bill sponsor have to pacify his own party, which is clearly difficult as it is, but he will now also have to worry about Brown. The platform of Brown’s campaign was representing the common man, and working to establish a political milieu that was conducive to real reform. Unfortunately, Brown seems to draw a parallel between combatting the nonproductivity that is ubiquitous on the Hill and vehemently opposing anything the Democrats propose.

Early on in his campaign, Brown reached out to many aggravated independents, most of whom had historically voted Democrat, in order to garner a sufficiently varied, and therefore large, voting base. Accordingly, Brown started out by assuming a dynamic stance on most issues, projecting himself not as a die-hard Republican, but rather as a champion of the people, with purely pragmatic and objective views.

Ultimately, however, Brown shifted his stance mid-campaign to position himself as the Republican lifeline to the Senate. His views on most crucial topics echo those of the most conservative Republicans and correlate little with the versatility he had originally promised his Democratic voter base. Regardless, Democrats in Massachusetts went on to vote him into Senatorship—a testament to the power and irrationality spurred by public frustration, with not only political inefficiency but also misaligned views.

The implications of Brown’s elections stretch far beyond the presence of a Republican proxy in Senate. If the GOP has its way, Brown’s election will only serve as a precursor to a much larger upheaval in the House of Representatives. The same resentments of closed-door deals and languishing legislation that skewed the vote in Massachusetts may manifest itself in other states. A Republican House of Representatives, voted in by irate citizens, would be disastrous for any of the legislation currently on the table.

With the American people waiting for deliverance on the change they were promised, the dynamics of Capitol Hill are more volatile than ever. Truly, the landslide election of a staunch Republican in a state as historically Democratic as Massachusetts emphasizes the magnitude of dissatisfaction that the American people harbor in the government they were once so enamored with. The American people are hoping that the Republican in a Democratic Senate will help purge Washington of partisanship and nonproductivity, but unfortunately, Brown’s election may just perpetuate it.