Every school morning at 1:30 a.m., Rayne Xue logs off her computer, having just finished yet another day of online learning. Despite being a sophomore at Tabor Academy, a boarding school in Marion, Mass., Xue now lives in Beijing, China.

While Xue’s situation is unusual, other students and staff in China have also experienced drastic changes to their schools. The country’s strict COVID-19 policies are reflected in schools, where infection prevention measures are still in place even though the country has seen few cases since April.

Since March, Tabor Academy has been giving students the choice between in-person classes and remote learning. Students can choose to live in dormitories there or return home and take classes online.

In the beginning of April, Xue returned to China because coronavirus case counts were under control there, unlike the rapid increase in the U.S. Because of China’s quarantine policy, Xue had to quarantine in a hotel room alone in rural Tianjin.

“I stayed there for 14 days and I couldn't leave my room,” she said. “School was difficult there because the internet was not stable.”

Afterward, Xue returned to her home in Beijing and started a routine of attending school over Zoom from 9:30 p.m. to 1:30 a.m. local time.

“For us ‘Zoomers,’ we log on with our computers, and the teacher will have our faces displayed up in front of the classroom,” Xue said. “We can see all of the in-person students and participate in class.”

After Thanksgiving, however, Tabor Academy will move to all remote learning for all of its 500 students, a response to the surging cases in Massachusetts.

While in-person classes have halted in tens of thousands of U.S. schools, they are going on in China, Xue said. She is participating in Onboard+, a program founded by Tabor Academy and several other U.S. boarding schools for their students in Beijing and Shanghai.

“We can meet students from other boarding schools, do our school work and participate in activities,” Xue said. “Every afternoon, I go there for musical practices and sports.”

After schools in China moved back to in-person education in April and May, severe pandemic control measures went in place.

Junior Elena Yu attends the Yew Chung International School in Shanghai. There, students receive twice-daily temperature checks and must stay one meter with others while wearing face masks other than when they eat. In the cafeteria, dividers have been built in between tables.

Unlike metropolitan schools, rural schools seem to have more relaxed policies. Junior Siyao Xiong, who attends Nanjian No. 1 High School, a boarding school in Dali, Yunnan Province, said that although she is still required to wear a mask upon entering her school, she is no longer required to wear it in class. (For the majority of high schools in China, students are in the same classes while teachers rotate in and out).

The same goes for Zhejiang Province’s Luqiao No. 3 Middle School. This is where my uncle, Lingbing Chen, works as an assistant principal.

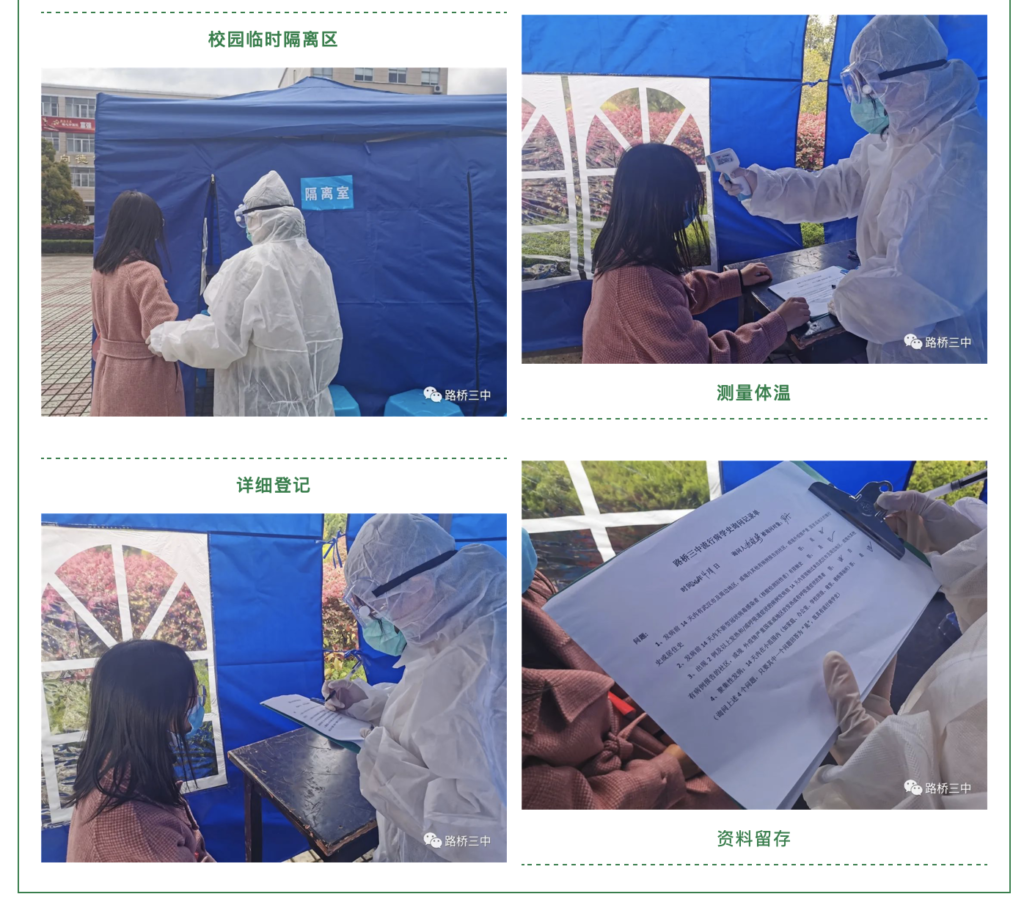

He told me that staff are not allowed to leave the city — and certainly not Zhejiang Province — unless there are special circumstances. Each morning, students’ temperatures are taken before they are allowed to enter the campus, which is equipped with isolation tents at the ready. In addition, large-scale indoor activities have been banned.

These are only a fraction of the detailed instructions outlined in numerous documents and flowcharts from the school and the education departments. To better orient students and staff to these instructions, the school ran a meticulous drill for every situation that could arise, including 11 different scenarios of finding a student with symptoms of COVID-19 and the appropriate responses to each.

“The most important thing we have is an optimistic attitude in face of challenges,” Chen said in a speech to the school. “With it, the so-called problems are not big problems.”

*Direct and indirect quotes from Yu, Xiong and Chen are translated from Chinese.