One time in eighth grade, a girl asked me a perfectly normal question: Do you play an instrument?

“Yeah, I play the Guzheng, the Chinese harp,” I said. A few months before this conversation, I had demonstrated the Guzheng in class and she had seemed mildly impressed, so I was somewhat confused that she didn’t remember.

After a moment of silence, the realization dawned on her face, and she replied, “Oh, I mean, do you play an actual instrument?”

I had studied the Guzheng for seven years by then, but it had always been something my parents forced me to do. Looking back, I realized that moment was what initiated my passion for traditional Chinese music.

I take issue with the line between traditional Chinese instruments and “actual” instruments, because Chinese instruments and instruments from any non-Western cultures are not primitive artifacts, nor are they exotic displays for curiosity. They are just like any other musical instrument because of their complexity and the stories they carry.

The Guzheng originated 2,500 years ago and has a history long enough to rival any western instrument. While an instrument that old might belong in a museum exhibit, the Guzheng has evolved: Its size grew and its strings changed from silk to steel. The version we play today, with 21 strings and taller than I am, was re-designed in the 20th century.

As someone who’s tried learning the piano and who teaches a Guzheng elective at a local Chinese school, I can tell you that the Guzheng is not easy. But I also understand where the misconception that the Guzheng is an easy instrument came from: If anyone drags their finger over random Guzheng strings, it doesn’t sound bad.

That is because the Guzheng — and all Chinese instruments — is in the pentatonic scale. To put it simply, no matter how you pluck the Guzheng, the combination of notes guarantee that it can’t sound horrible. That, coupled with the fact that the Guzheng doesn’t make the appalling screech a violin novice might make, gives an illusion of easiness.

Another reason for the girl’s dismissal of the Guzheng’s legitimacy is the perception that Chinese music equates to Zen music. If you search Chinese music on YouTube, you find hour-long meditation soundtracks with tranquil nature scenes as thumbnails.

But while the Guzheng does produce slow and calming melodies, that’s not all it can do. Especially after the 20th century, Guzheng composition shifted toward pieces that are stronger and livelier, with the most iconic piece being “Battling the Typhoon” — the title should be explanatory of its style.

Playing these fast and ferocious pieces requires years of practice to build up the necessary strength and speed. My left hand’s fingers are calloused from pressing the glissandos, while with the technique tremolo, I can strike a string with my right thumb 18 times in one second.

The Guzheng is far from the only traditional Chinese instrument. There are countless others — Dizi (bamboo flute), Erhu (two-stringed fiddle), Pipa (Chinese lute) — each with their unique histories.

All of these instruments work together in Chinese symphonies, which are often divided into four sections: plucked strings, bow strings, wind and percussion. During the time I played for the California Youth Chinese Symphony, I was astonished by the wide range of music styles we could perform.

But as much as traditional Chinese instruments should be taken seriously, they should not be fetishized. Too often, Chinese and non-Chinese alike pose in front of my Guzheng to take pictures (sometimes without permission). This extends into cinema, such as in the movie “Our Shining Days,” in which the iconic showdown between traditional and western instruments is portrayed far too dramatically.

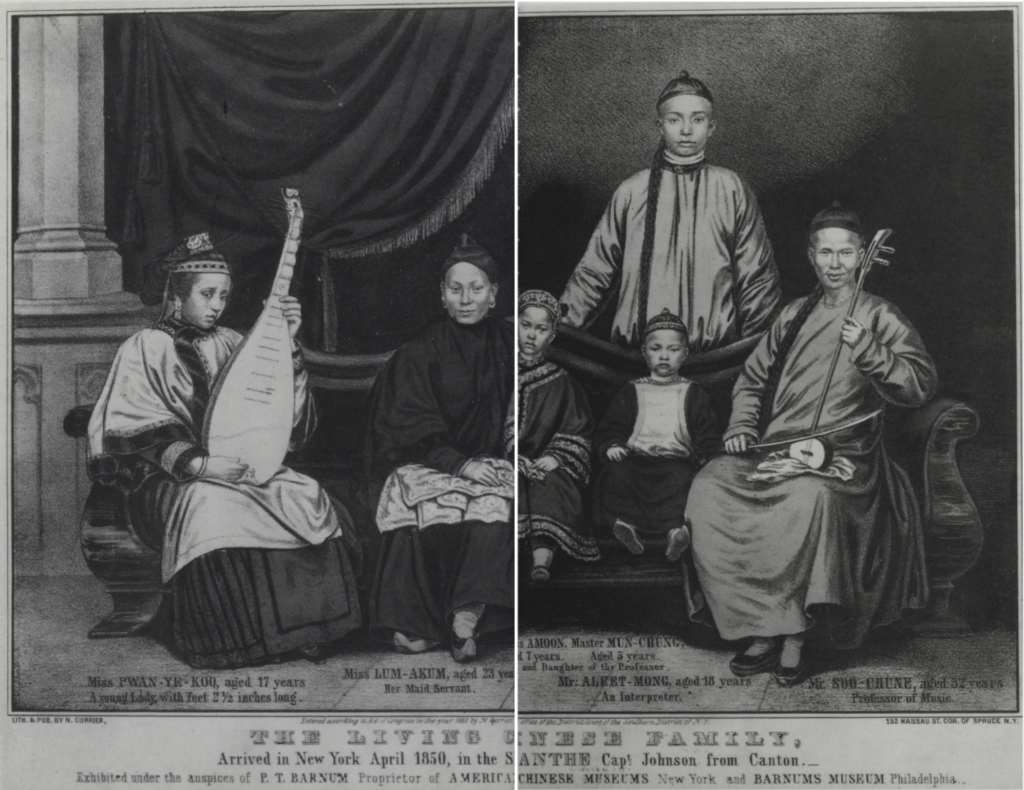

The people marveling at Chinese instruments they had never seen before are unaware of the dark history behind America’s fascination with them. In 1850, the first Chinese immigrant musicians were exhibited with their musical instruments in P.T. Barnum’s museum as strange members of the human race and exotic attractions. The photo, titled “A Living Chinese Family,” was of the exhibit that curious Americans paid to see.

Despite a racist past that has contributed to this current dichotomy, I see hope for traditional Chinese instruments to become recognized as an equal to other instruments.

In 1986, a New York Times article defined ethnomusicology as “the study of any music unfortunate enough to be non-Western.” It reported that “we still don't have much idea how most of this music actually sounded.”

Since then, immigrants and touring performers have made efforts to spread traditional Chinese music. In 1999, my Guzheng teacher Chiffon Fu held the “Love of Guzheng” concert in San Francisco. Then Governor Gray Davis called it “the most beautiful music ever brought to California” and set Sept. 23 as California’s Chiffon Fu Day.

In 2012, the Guzheng appeared once again in The New York Times. In this interview, two traditional musicians who played for President Obama said that in the 1990s they thought “the more Western, the better.” But “that kind of thinking is no longer dominant” because “the music of our ancient China is … not at all inferior to Beethoven or Tchaikovsky.”

I can’t express how important the Guzheng is to me — after all, a miniature Guzheng was what I carried on my back five and a half years ago when I stepped into the San Francisco airport as an immigrant to America. Erasing the line between traditional Chinese instruments and “actual” ones helps bring acceptance and legitimacy to Chinese culture and identity.