Not even Nextdoor is safe.

Nextdoor used to be about giving neighbors restaurant recommendations or tips on which plumber to hire or funny neighborhood pictures. In recent years, though, it has sometimes devolved into messy political statements and even occasional threats.

With the election having just passed, political polarization in the U.S. is at an all-time high.

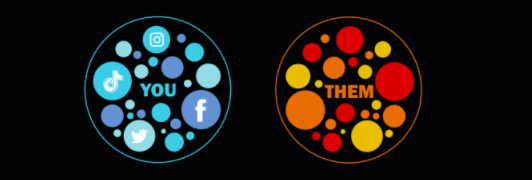

Yet as users continue to turn to social media as a source of political news, this polarization is exacerbated by social media app features that show users posts that are more likely to resonate with their political beliefs in the so-called echo chamber effect.

This phenomenon is prevalent on the video-sharing platform TikTok, whose 800 million users are enticed by its For You page, which is tailored toward individual users. TikTok groups its users into clusters based on their interactions with videos — commenting on, liking or simply scrolling past them. As a result, as the preferences of users become more refined, the For You page gradually gets narrower in scope.

While this feature may seem beneficial to users, who use the app to watch what interests them, studies show that it results in a lack of exposure to people of different backgrounds. In fact, a UC Berkeley School of Information researcher discovered in a casual experiment that following anyone resulted in suggestions for people from similar racial or ethnic backgrounds. TikTok attributed this to “collaborative filtering,” where recommendations are made based on the actions of other similar users.

TikTok is hardly alone. A study showed that Facebook is undergoing an almost identical issue: As users fail to engage with and respond to posts, similar posts start to appear less frequently. Users with more extreme views tend to continue consuming more extreme content with no exposure to other perspectives.

Junior Ishanya Hebbalae has been using social media — particularly Facebook and Instagram — as a political news source since seventh grade. She said that most of the news she reads from it is fairly liberal, especially when it concerns human rights and the environment.

“As a result, my views have shifted a little bit to the left,” Hebbalae said. “Social media does have its drawbacks, but when coupled with reliable sources, I find that it is a convenient way to obtain information.”

However, some social media platforms, like Twitter, have a larger issue aside from just the algorithm: a large-scale echo chamber partially generated by its users’ demographics. A Pew study found that Twitter users are more likely to identify as Democrats than Republicans than is the general public. This difference is apparent in the overwhelmingly liberal replies to posts by both @TheDemocrats and @GOP.

“People who disagree with the opinion of the post creator often get a lot of backlash and ad hominem attacks,” said junior Miwa Okumura, a Twitter user. “It is rare to see civilized discussions of opinions.”

Okumura, unlike most of the users she has observed, attempts to minimize polarization within her feed. Although most Twitter users are left-leaning, her feed is roughly equally split between left- and right-wing opinions. To achieve this distribution, she follows people from both sides and regularly goes back to their accounts to compare their opinions with others’. She also likes and saves posts for future reference.

“Witnessing the extremes of both political spectrums has helped me to bring myself to see the best in both sides and find a middle ground,” Okumura said.

However, while few users go to such lengths, those who do may actually be strengthening their existing views despite being exposed to the other side. A study revealed that attempts to establish common ground backfired: Republicans tended to adopt significantly more conservative views after following a liberal Twitter bot.

Regardless of the true causes of polarization and echo chambers, experts have some solutions to resolving polarization generated by social media-created echo chambers. In the short run, to expand the range of opinion-based posts we see, Wired recommends following Okumura’s lead: “liking” every post users see, searching for reliable news on both sides of the political spectrum and changing feed settings from “personalized” to “recent” in order to avoid being placed into clusters by algorithms.

In the long run, UC Berkeley suggests that we establish more meaningful intergroup contact, where people come together to establish common ground; bridge our differences by identifying ourselves as humans rather than as Americans; use proportional voting; and vote on policies rather than parties.

Hebbalae suggested another step toward reducing the potential for radicalization and hence polarization: ensuring that social media posts are at least accurate.

“Social media news stories are really just snapshots of the actual story because they’re designed to get the viewer’s attention,” Hebbalae said. “Making it more reliable is especially important now that more and more people are turning to it for news because of its convenience.”