In a blush pink bikini, Calyx King, a junior at Los Gatos High, dances to Beyonce’s “Crazy in Love” behind white text stating, “Gentle reminder that just because someone’s body is naturally what you view as ‘desirable,’ doesn’t mean you get to sexualize them, nor does it mean you can shame people who don’t look like them. No one is asking for it.”

Although some of the comments are positive, many of them attack her with messages like: “but you are a whoooorrree,” “wrong ita a free country i can secualize whom i feel is desirable” and “snowflake logic.”

King, who started her TikTok in last September and became active during quarantine, posts body-positive, leftist, anti-racist and anti-sexist content that has garnered her over 15,000 followers.

Many creators like King have produced content in response to the many misogynistic trends that have also gained traction on TikTok.

Junior Naomi Malik believes that one reason misogynistic TikToks have become popular is that the app makes it easy for people to participate in misogynistic trends.

Although the app was launched only in late 2016, according to Datareportal, as of July, it had over 800 million active monthly users. This, combined with the low-effort user interface, makes it easy for anyone to have access to a large audience.

“It’s easy to edit and make videos, which means that people don’t have to go through a lot of trouble to get their message out,” Malik said. “They don’t have to think about it as much and who it will affect.”

Malik, who started her TikTok in December 2018, has seen several misogynistic jokes in the comments of her TikToks.

“I’ve had some derogatory comments in the past on my page about how ‘girls aren’t funny’ and jokes about my looks,” Malik said.

Malik isn’t alone in receiving such comments. One recent trend is that users rate women based on their appearance, with a number 1-10 for their upper body, a number 1-10 for their lower body and a letter grade for their face. This form of objectification often goes unrecognized since creators rate women in the comments in a discrete way.

But some are less discrete in their objectification.

“Whenever I stand up for myself or other victims of misogyny, I’m often slammed with the comments like ‘It’s a man’s world, you girls need to realize that,’ ‘someone should r*pe you,’ and so on,” King said. “I get told to put my body away when I’m doing fun dances that don’t cover every inch of my body. I am called an object.”

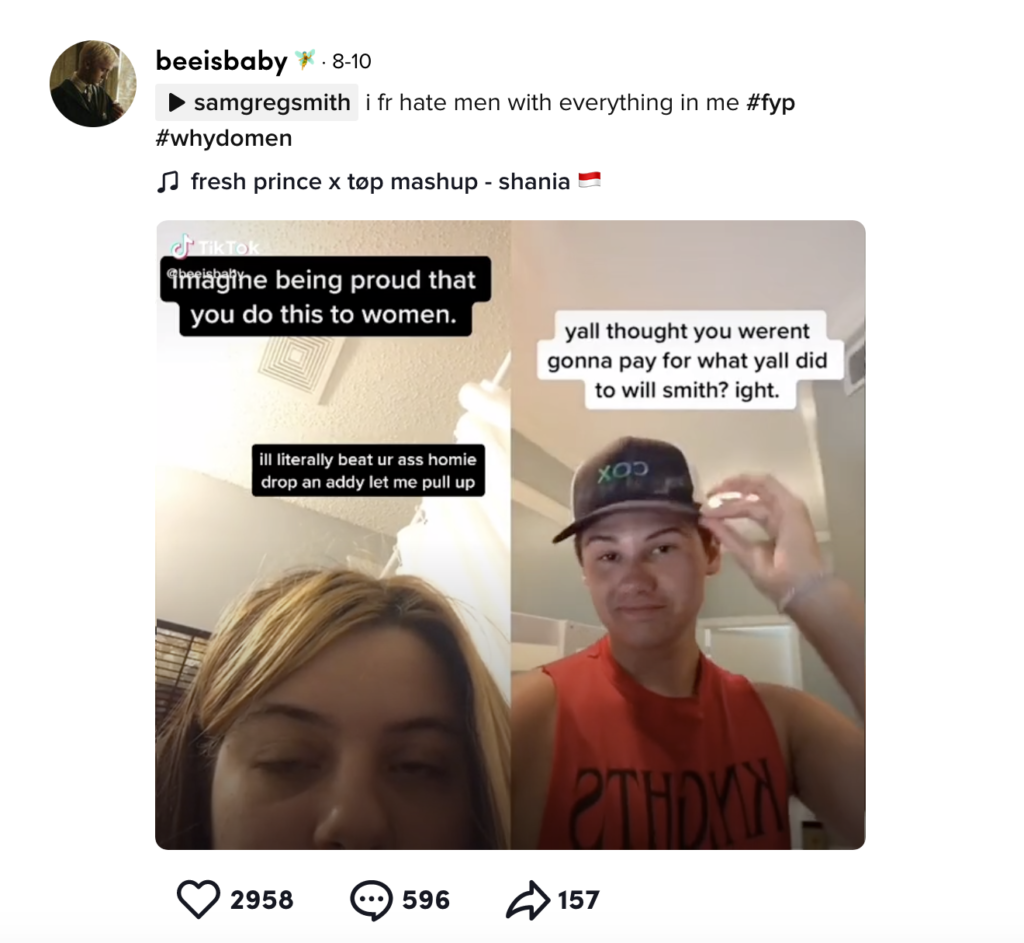

On top of objectification, boys on TikTok have also started a trend of harassing women as a form of “revenge” for Will Smith. The videos were in response to Jada Pickett Smith, who was on a break from her open relationship with Smith, getting into an “entanglement” with August Alsina in 2017.

The videos, set to a remix of Smith’s “Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” and Twenty-One Pilots’ “Heathens,” show users, usually white boys, bragging about how many girls they have made cry, delete their accounts and block them, sometimes with accompanying screenshots of crying faces or text histories.

While some of these TikToks are fake, with captions like ”I’ve made 389 girls go private, 103 cry and 89 delete their account,” they still convey a misogynistic message that trivializes the act of harassing women, and often get praised with comments like “That’s my boy.”

The creator of the sound, junior @wtfshaquena, has also deleted the original video in an attempt to get rid of the sound and the videos that use it.

She posted the video on musical.ly in 2016, but it resurfaced this year as the soundtrack to the revenge trend. When @wtfshaquena had realized that her sound had been taken over, she didn’t speak out because she didn’t feel like she had a voice against them.

“I think people feel comfortable making these trends because they have a whole community that will defend someone when they post controversial content like the ‘revenge for Will Smith’ TikToks,” @wtfshaquena said.

To make matters worse, the sexist content seldom receives punishment or removal from the app itself.

“It’s a free app that does a very poor job of monitoring what people are posting,” King said. “For example, I was trying to make a video educating people about domestic terrorism and it took the video down because of the word ‘terrorism.’ Then it leaves other videos saying that ‘Only one in 5 women are r*ped? Men need to step up our game. This kind of flawed algorithm gives people keyboard courage. This easy access is dangerous.”

Despite TikTok’s Community Guidelines, which state that content that “sexually harasses a user by disparaging their sexual activities or attempting to make unwanted sexual contact,” claims that a group is “physically or morally inferior,” or “disparages a private individual on the basis of attributes such as intellect, appearance, personality traits, or hygiene” will be removed, the company has often failed to follow through.

According to New18, in India, the app was briefly banned in April 2019 for being “responsible for spreading sexually abusive content that could affect children while also exposing them to sexual predators.”

While the app often fails to catch sexist content, many creators have taken it into their own hands to call out and create backlash for it. Currently, the majority of the 129,000 videos that use @wtfshaquena’s sound are not following the original trend. Many of the most popular videos are now of people criticizing the previous use of the sound, or state how many women they have complimented instead.

“I feel that users combating sexist trends, content and users is absolutely necessary,’ King said. “If we are silent, then we are compliant. It is absolutely crucial that we use our voices and educate those who are perpetuating such harmful ideas and concepts.”