When California Gov. Gavin Newsom first ordered shelter-in-place last spring, senior Eileen Sun planned to keep in touch with all of her friends, communicating with them as if everything was normal. Now, more than six months later, she says she regularly talks to only three of them.

“It just got to be so much work trying to find new conversation topics that we could actually carry on,” she said. “I guess we didn’t have much in common in the first place.”

For many, the pandemic has cut down on the number of friends they have. Quarantine has unintentionally exposed the ways relationships are maintained in regular in-person life. Some scientists posit that there is a specific limit on the number of true close friends most people can have in their daily lives under normal circumstances.

In a 2014 interview with The New Yorker, professor Robin Dunbar of Oxford University presented his discovery about the limit of human friendship, dubbed Dunbar’s number.

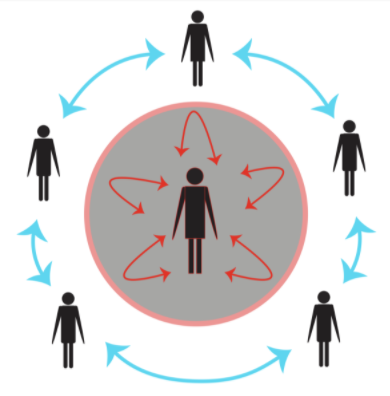

Dunbar concluded that the average person has 150 people in their casual social group, which is around the limit of meaningful human relationships people can have. This group of 150 is divided into different layers based on closeness. The next smaller circle in the 150 group is 50 people, who Dunbar labels as close friends, albeit not very involved in one’s life.

To narrow those numbers down further, most people have 15 friends they are able to generally confide in. In the most intimate group, which also includes family, the number is five.

Since Dunbar’s number is based on normal social interactions, it makes sense that meaningful relationships in quarantine, which consist of far less in-person social activity, can decrease even more.

Other factors also contributed to Sun’s loss of communication with friends: In the midst of a pandemic or any time of stress, people may find themselves too busy or concerned about other aspects of their lives to put in the effort required to keep close relationships.

This was the case for Sun. She was stressed about her grandparents, who lived near Wuhan in the beginning of the pandemic. She was also extremely concerned about her parents, because she thought they were not taking the crisis as seriously as she was.

To add to the tension, Sun said she felt overwhelmed and crowded by her entire family working from home all day while she participated in online classes. Her parents had more conflicts than usual, and while they never took it out on her, she occasionally blamed herself.

“I think family conflict was probably part of the reason why I haven’t talked to some of my friends,” Sun said. “But I hope it isn’t awkward when we go back to school. It was really nothing personal against anyone else.”

But in such a long period of quarantine, household stress is not the only issue affecting relationships.

A few weeks after the shelter-in-place was ordered, Jessie, a pseudonym for a sophomore girl who asked to be anonymous, reached for her phone out of habit to check her texts, only to realize she hardly had anyone to contact. After a couple more weeks passed, she was only receiving occasional brief messages, a stark difference from the 30 or 40 notifications she had been receiving almost daily.

At the beginning of quarantine, Jessie stayed up late talking with her friends through Snapchat and FaceTime. But as the initial excitement that came with the shelter-in-place began to die down, so did her communication with friends.

She vividly remembered when a close friend, someone she had known since seventh grade, didn’t wish her a happy birthday.

“We hadn’t talked for a few days before that, which was kind of weird, but I was really surprised when she didn’t text me at all that day,” she said. “It really hurt me.”

Jessie had thought that they were close friends before and was confused and upset when they stopped talking. Even though she received messages from her other friends, she still felt isolated.

Jessie, who has struggled with depression since freshman year, said she found herself overthinking things she had said in the past. She began to consider what she might have done wrong. Oftentimes, she felt completely alone.

She wasn’t the only one feeling this way. A Johns Hopkins study conducted in April found that, compared to a similar study from 2018, there was a three-fold increase in people reporting psychological distress from quarantine, with common stressors being anxiety from social isolation and loneliness.

After her birthday, Jessie stopped communicating with most of her friends, even ones she had known for years. When they didn’t seem to notice, she said she felt as if they didn’t want to keep in touch with her because they would have otherwise reached out themselves. For a period of time,she wasn’t in contact with anyone, and she “thought everyone was happier that way.”

“I felt like no one cared about me,” she said. “I was in a really bad mental state and sometimes was just wondering why no one was trying to talk to me.”

Despite new social media platforms like Houseparty and Netflix Party popping up to replace — or at least simulate — face-to-face interaction, many friendships have crumbled over quarantine.

According to Psychology Today, studies have shown that relationships are easier to maintain when physical interaction is involved. The long-term effects of limited in-person social interaction can nearly double a person’s risk of depression, but even a face-to-face shared laugh can immediately increase production of endorphins (stress-relieving chemicals) in the brain.

But sometimes, even without any physical interaction, relationships can be revived.

When Jessie received a message from a friend she hadn’t spoken to in a while after a long period of self-isolation, she remembered smiling and feeling “really happy.”

“It was really nice to think that someone actually wanted to talk to me,” Jessie said. “I had kind of convinced myself that everyone was better off without me.”

She reached out to some more friends afterwards, and while some conversations died out again, she was able to reconnect with a few friends just by catching up about their lives and having deeper conversations.

“I kind of learned who I’m closer with during all of this,” she said. “I’d say I have some stronger relationships with people now, and maybe less casual friends. In a way, I feel OK with that.”

If you are feeling lonely or struggling with anything, there are resources available to help. CASSY can be found at:

https://www.saratogahigh.org/guidance/c_a_s_s_y_student_support_services

Or call these hotlines:

Mental Health Call Center: (800) 704-0900

SAMHSA: 1-800-662-HELP (4357)

24-7 Teen Line (Bill Wilson Center): 1-888-247-7717