As a high schooler, 2000 alumnus Andrew Bosworth brought pigs, sheep and guinea pigs from his family’s farm to the country fair. Two decades after leaving the school to attend Harvard, he is the vice president of virtual and augmented reality at Facebook.

Bosworth, who goes by his high school nickname Boz, left his job at Microsoft in 2006 to work with Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg on the new startup called Facebook.

Zuckerberg reached out to Bosworth a year and a half after Bosworth was Zuckerberg’s instructor in an introductory artificial intelligence class. A month after the course ended, Zuckerberg launched Facebook, and Bosworth joined the next day as Facebook’s 1,681th user.

Although he was torn between the established company and the startup, his manager at Microsoft, who Bosworth said invested a lot in him early in his career, advised him that he had nothing to lose.

That, Bosworth said, was the first time that he got off the “track” — the plan that he was expected to follow from high school to college and eventually, a decent job.

Bosworth said he believes “when you're young is when you can take the most risk” — risk that ultimately led to him being “very lucky.” The decision to join Facebook is one he is proud of to this day.

“Even if Facebook had not amounted to what it is today, [taking the opportunity] was an amazing experience that I wouldn't trade,” he said.

Bosworth explained that his experience at the company has been so rewarding because of the amount he was able to learn about new tools and coding languages while navigating roadblocks and failures with little guidance.

“There was nobody to ask for help,” he said. “There's no teacher, no boss, there's no structure. It’s usually you and the problem, and if you didn't solve it, you let your colleagues down.”

This mindset is what allowed Bosworth to experience what he called “real engineering,” which led to him and one other person building Facebook’s pioneering newsfeed function on their own.

The technical failures — when he tried things and they didn’t work — could be satisfying, he said. But he regrets the occasional interpersonal failures, where he failed to build a relationship with someone or failed to connect their talents in a way that allowed them to produce something greater.

Bosworth said this second part, the social-emotional component of leadership, was just as important as his computer science skills in the startup. Now, reflecting on how far his relationship-building skills have come, Bosworth admits to feeling haunted by his 20-year-old, loud, sometimes aggressive self.

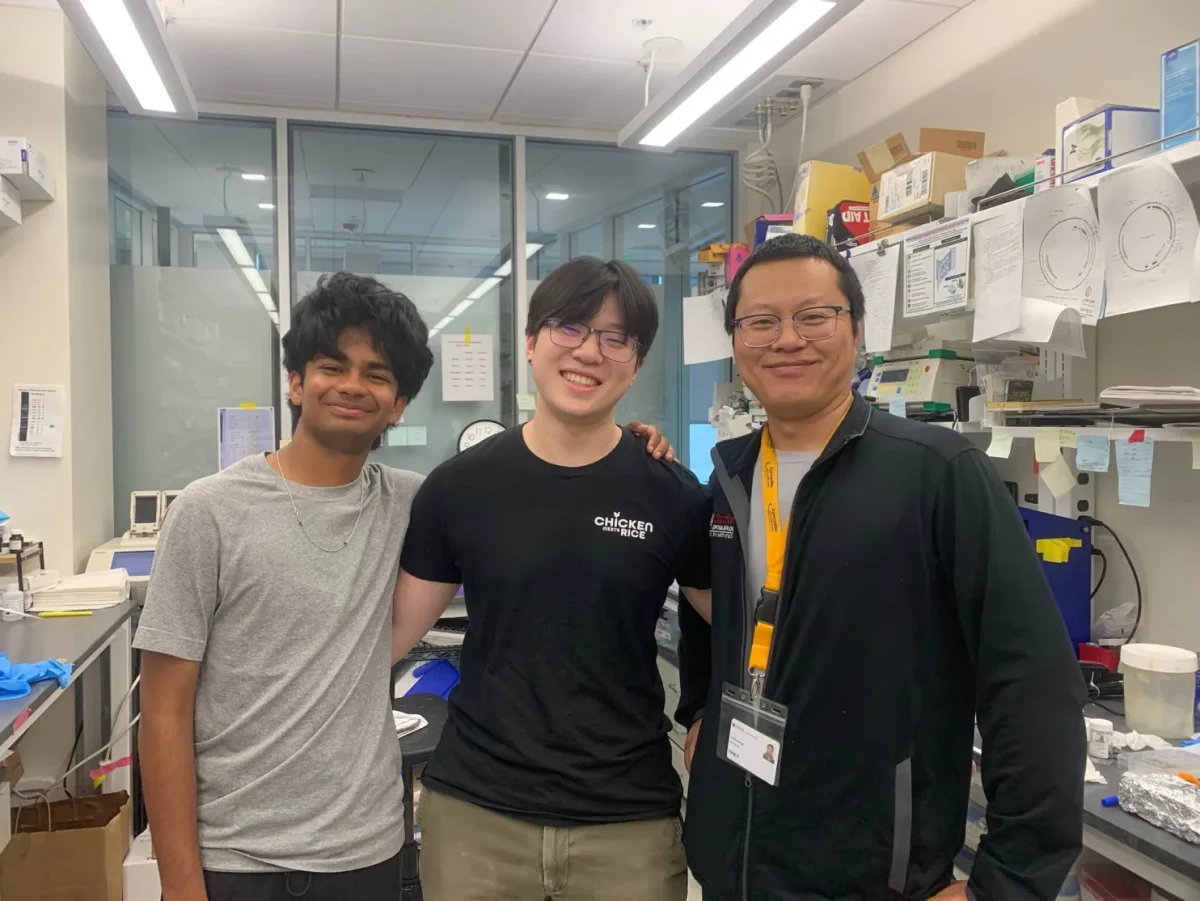

But today, with a much greater understanding of the degree of responsibility he has when interacting with other people, he’s had a lot of fun meeting new people and recollects the joy of running into old classmates. As a result of old connections, Bosworth has been able to work on a number of projects with fellow alumni such as Jaime Merz, who runs a design firm, and Adam Freeman, who has a construction company.

“There's some kind of a camaraderie that high school builds,” Bosworth said. “The networks that we had in high school may not stay intact that long, but the camaraderie that’s formed by having a common background is a powerful tool throughout life.”

Defending controversial opinions

Bosworth has gained a reputation in recent years for his frank opinions, often critical of Facebook. In 2016, he released the controversial memo titled “The Ugly.” In it, Bosworth stated that Facebook was founded with the primary mission to connect people, and “anything that allows us to connect more people more often is *de facto* good.”

He said that Facebook may connect more people while also costing someone’s life in a terrorist attack coordinated with Facebook’s tools or by exposing them to bullies.

Bosworth later stated that he never agreed with the post, and that he wanted to “bring to the surface issues I felt deserved more discussion with the broader company” and said “I care deeply about how our product affects people and I take very personally the responsibility that I have to make that impact positive.”

In response, Zuckerberg stated that he disagreed with Bosworth’s statements, writing, “We've never believed the ends justify the means.”

However, both Zuckerberg’s and Bosworth’s perceived prioritization of all-encompassing growth is a stance that some still find to be a form of manipulative treatment of data and users — a sentiment that Bosworth discussed in January 2020, when he released an internal memo that was obtained by The New York Times stating that the company should not change its policies on political advertising.

“As tempting as it is to use the tools available to us to change the outcome, I am confident we must never do that or we will become that which we fear,” he wrote in the memo.

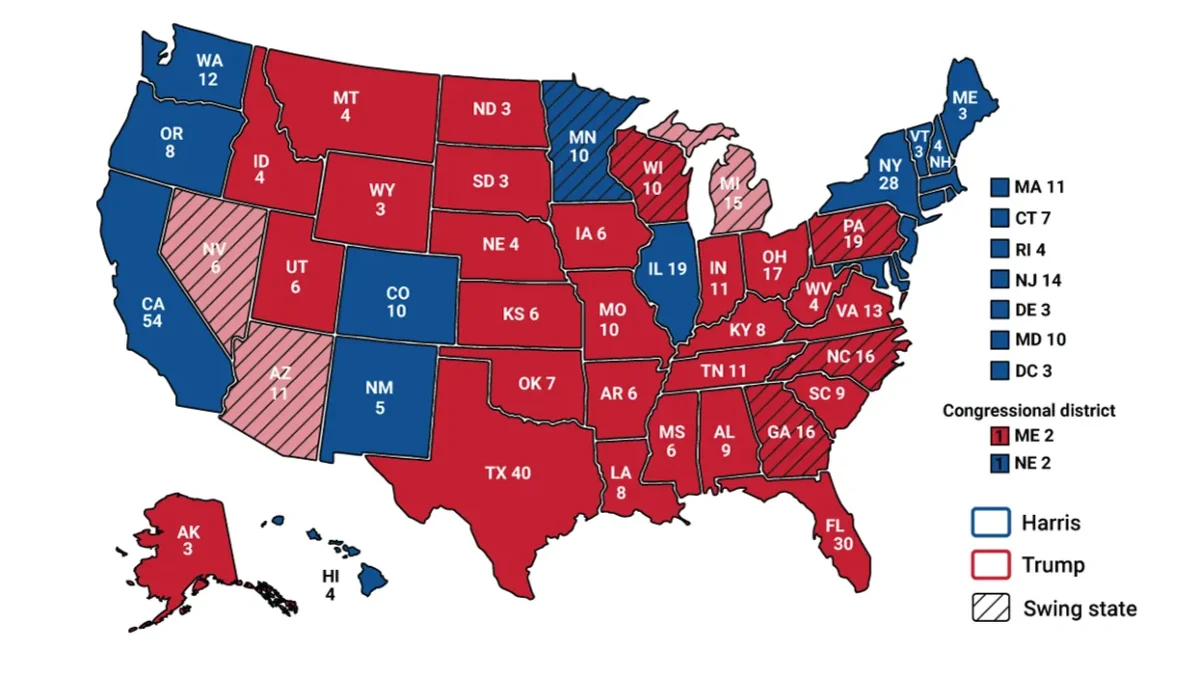

Bosworth, who is politically liberal, oversaw the ads organization of Facebook during the 2016 election and had been doing so for four years prior. He said that Trump was elected not because of misinformation or foreign interference, but because “he ran the single best digital ad campaign I’ve ever seen from any advertiser. Period.”

At the same time, Bosworth acknowledged that Facebook was late in their response to data security, misinformation and foreign interference, and believes the company needs to get ahead of polarization, algorithmic transparency and any other contentions in the future.

A football player who loved technology

In high school, Bosworth was a star athlete who was named Athlete of the Year, set records and earned all-league honors as a linebacker on the football team. In 2011, he was celebrated in the Saratoga Sports Hall of Fame, and in college, he became a NCAA Tae-Kwon Do Champion.

Off the field, he used his Photoshop skills to create “freelance graphics” for The Falcon and was heavily involved in 4-H, a large youth development organization whose mission is to “empower young people with the skills they need to lead for a lifetime,” per their website. In fact, while he spent a lot of time there nourishing his love of raising animals, a friend from 4-H first taught him how to program. And in 2019, Bosworth invested $1 million into 4-H STEM.

Now a father, Bosworth cultivates hobbies such as photography and writing that he publishes on his blog.

Twenty years into his career and having had the opportunity to follow some of his classmates’ careers, Bosworth believes that his satisfaction and happiness in his job was a luck of the draw situation. Although it worked out for him, Bosworth doesn’t recommend young adults stay on the “track” for as long as he did. Instead, he thinks they should figure out what they really want to accomplish, and take risks.

“Don’t put your hobbies on the shelf,” he said. “It's easy to be the cookie cutter kid. It may take a lot of time and energy, but you look like everyone else. Is that really what you want?”

In high school, Bosworth wasn’t in the top of his class; in fact, he said he thinks he “barely snuck” into honors. Yet he was the only student in his class to be admitted to Harvard because admissions officers saw something in him.

He said that he believes many people who succeed in school and business invest in their own interests — his being agriculture and raising pigs — which allows them to be more well-rounded and see opportunities that other people don’t see.

Since he grew up in the Silicon Valley during the dot-com era, Bosworth said he always imagined himself becoming a tech executive and believed that it was something he could do, although he acknowledged that it took a lot of luck and more work that he had imagined.

“This is, weirdly, exactly where I thought I’d be,” Bosworth said. “I really had no business to believe that except for, I think, a healthy dose of naivete.”