Last semester, Matthew Welander’s AP Physics class experimented with using a peer-grading system via Canvas, which automatically assigns a student’s work to an anonymous peer-grader in the class. The peer-grader plugs appropriate point values into a rubric, which enumerates the parameters on which the work is graded.

Welander started using this system this fall, after students in the class said that they would rather that he spend time curating review materials for tests than grading students’ labs.

Thus, using the Canvas peer-grading that students can complete outside of class time, the 15 to 20 minutes spent grading each lab is distributed among students, cutting Welander’s grading time to around two hours.

Two students grade each lab, which are worth 25 percent of the overall grade, but the grades are looked over by Welander. If a student contests a score given by peer-graders, they can approach Welander with their grievances.

Peer grading, while not ubiquitous, is used by other teachers on a variety of assignments.

For example, Spanish teacher Bret Yeilding has utilized the peer-grading system for almost 35 years for many of his assessments.

After finishing a quiz, Yeilding redistributes the quizzes randomly to students, instructing correctors to take out a red pen and sign their name at the bottom of the page. Students carefully check if answers match those projected to the board; if not, the answer is automatically wrong — Yeilding does not field questions from correctors unsure of a response’s veracity.

Afterwards, Yeilding double-checks all of the peer-graded responses and corrects the open, complex sentence response portion. He thinks that reviewing answers immediately after the quiz benefits the learning process.

“I like them to be able to see the answers immediately; that way, they’re making the connection between right and wrong,” Yeilding said. “It also helps me with the busy work. That way I don’t have to do 60 to 90 pages of vocabulary or fill-in-the blank items when the class can do that in 2 percent of the time it would take me.”

Despite its use by many teachers, peer grading has its critics. Yeilding said that some of his colleagues over the years have criticized his method of peer grading for perceptions of laziness or risk of cheating.

However, like many teachers at the school, he has rarely had issues with attempts at cheating, and certainly not enough to merit a retirement of peer-grading in the classroom. Yeilding said he always checks the peer grade since it’s easy to recognize when someone tries to fake someone else’s handwriting.

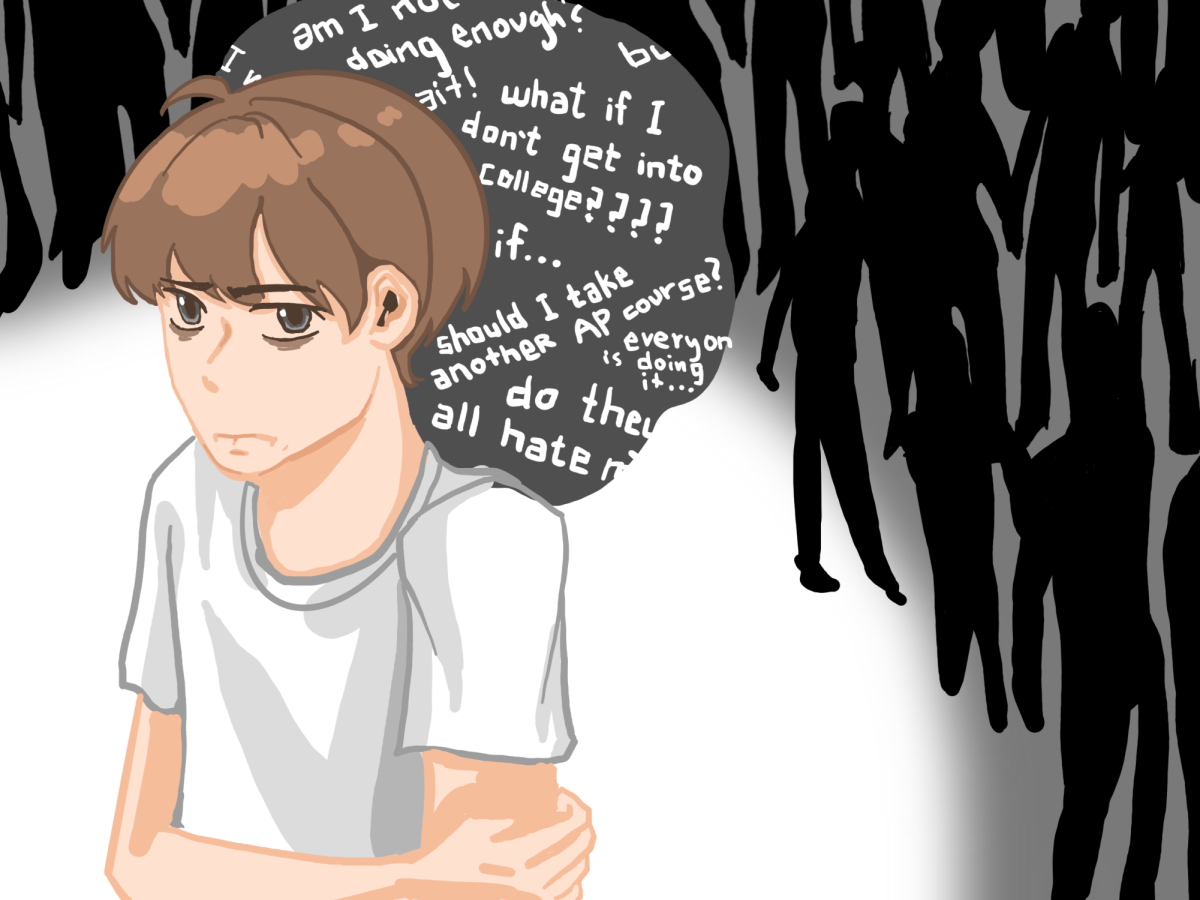

For students, peer grading tends to be a straightforward process, but it does require extra time in-class or at home, yielding an ambivalent relationship for most students.

Junior William Yin, a student in Welander’s AP Physics class, said that although the additional take-home assignment only took him around 20 minutes to complete and is relatively straightforward, it can be tedious to thoughtfully decide on grades.

Yin’s primary concern with the system is its tendency to lead to irregularities, especially with the more complex labs. While some students offer thorough, insightful feedback, others merely provide perfunctory comments.

“I feel like it’s really unbalanced [because] a lot of students are really lazy and just give full scores to everybody else’s projects, while other people actually put [in] effort and grade it based on its quality,” Yin said. “People get grades they don’t deserve or get grades that are worse than what they are supposed to get.”