It was a Sunday in Feb. 2018 around 4 p.m. when I found out some of the saddest news I had ever received. The sun slanted into the room, completing the lazy-afternoon feeling that came with most Sundays.

I was sitting on the couch at home when my mom’s phone rang. My father was on a plane ride to Madurai, India, to visit my family. I knew that my grandfather’s health was worsening; the news I dreaded could come at any moment.

I watched as my mom picked up the phone, talking in the polite tone reserved for relatives. A fear gripped me, coiling itself around my heart and squeezing. I watched as her face dropped.

And I knew.

All I could feel was an explosion of emotions as I registered that I would never see my grandfather again.

Fear cut through all the emotions. I feared for my father, who was on a plane. Who did not know the news about his father. Who would probably find out on his own in an airport millions of miles away.

As my mother wrapped her arms around me in an attempt to hold me together, I began to cry. I cried out of sadness, out of fear, but mostly out of shame. I cried out of the shame of knowing that I hadn’t fully appreciated the time I had with my grandpa when I visited my relatives in India a couple weeks prior to hearing the news.

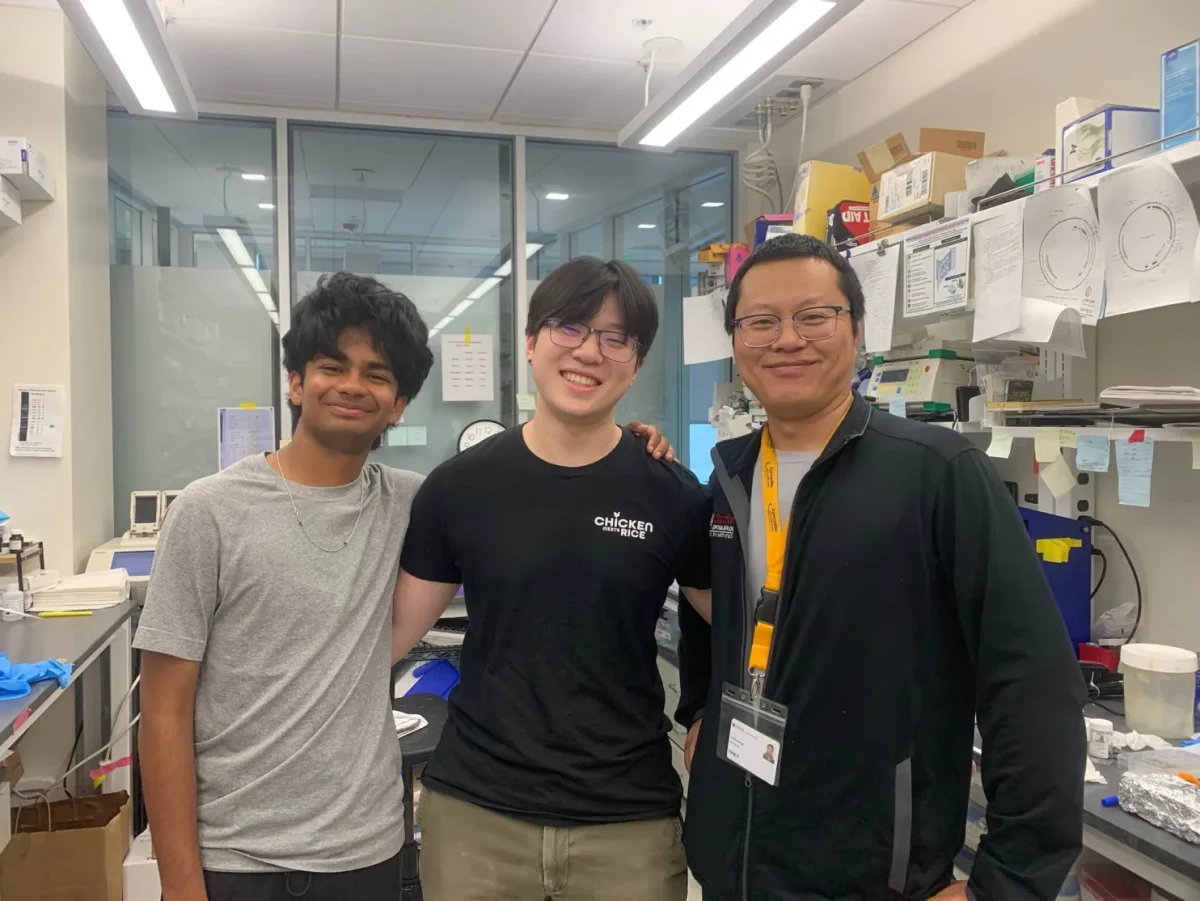

My grandfather, P. Marimuthu, was a professor of electrical engineering in India, and he had two sons. He was a shorter man with a slight stature and skinny frame who radiated a sense of self-sufficiency. He was on the quieter side: the type of person who you knew was intelligent by the way they observed the world. He was content to entertain himself through reading books and following the news.

My parents found out about my grandfather’s prostate cancer in 2009. He underwent treatment for years and was cared for by my aunt and uncle, but by 2018, they gave the call that we should visit soon. He passed away a week after we visited at the age of 79.

When I visited my family in India shortly before his death, I entered a familiar room upstairs — the room that, as a child, I would find myself in to take biscuits from my grandparents or to coerce them to play with me.

The room was different from before, not because of how it looked, but because of the thickness of the air surrounding me. It was dark, with the curtains drawn shut. The fan’s whirring was the only sound, and the smell of disinfectant penetrated the air.

My grandfather lay among blankets, looking thin and frail. He had lost a lot of weight and was awake for very short periods of time. I could tell he hated being bedridden. My grandfather was independent, and he loved to feed his mind with books and news, but his diminished state had left him weak and dependent on others.

I knew that I was expected to liven the sad, bleak room. Although I knew no one was expecting me to perform miracles, I was not even able to bring some sort of light into the dark room. I just sat in the room, feeling uncomfortable at seeing him in such a fragile state. I was used to my grandfather being the independent, studious man, not someone with such a fragile hold on life.

I could not think of a way to lessen his misery and to ease the anger he felt toward his illness. I wished that I was older; I wished that I was younger. I was 15 — at the age where I understood the situation, but I did not know how to act. If I had been a couple years older, maybe I would have had some extra wisdom. Perhaps if I was 5-years-old instead, I could run up and flash a big smile and bam — a miracle would have occurred.

Instead, I just sat there, wishing to be somewhere else because it hurt me to see my strong grandfather weak. Like my father, he was a constant supportive presence. He did not feel the need to make himself the center of attention, but he always showed his affection by gifting expensive presents, telling my father stories about me and playing cards with me.

Due to cultural differences, bonding with my grandparents was sometimes hard. Part of this was the language barrier — my grandparents spoke enough English to carry a conversation, but they preferred Tamil, which I can’t speak.

I also didn’t visit India often, and even when I did, the difference in dynamics between elders and children in India caused me to hold back. In India, it is a social norm for children to stay quiet out of respect.

I sat there in silence, day after day. When my grandfather called for me, I hurried upstairs, saying one or two words, like “yes?” or “I’m here.” Only on the last day when my mother read to him did I realize that I could have found ways to be truly present with him.

That trip to India and the experience of hearing the news were two of the most difficult moments of my life. There were days after my grandfather’s passing when part of me believed I could fly to India and he would be there, sitting in his chair as always. There were days where it hit me that he was truly gone; those were the days where I felt the most sadness and regret.

Most of all, I regret not spending more time with him while he was alive. I was young, and I did not get to know him well enough. As I grow older, my father shares stories about my grandfather — his impact, his mannerisms and his passions. I had more in common with him than I knew at the time. While my parents both started as engineers and went into STEM fields, I found myself being drawn to the humanities, as he had done when he was younger.

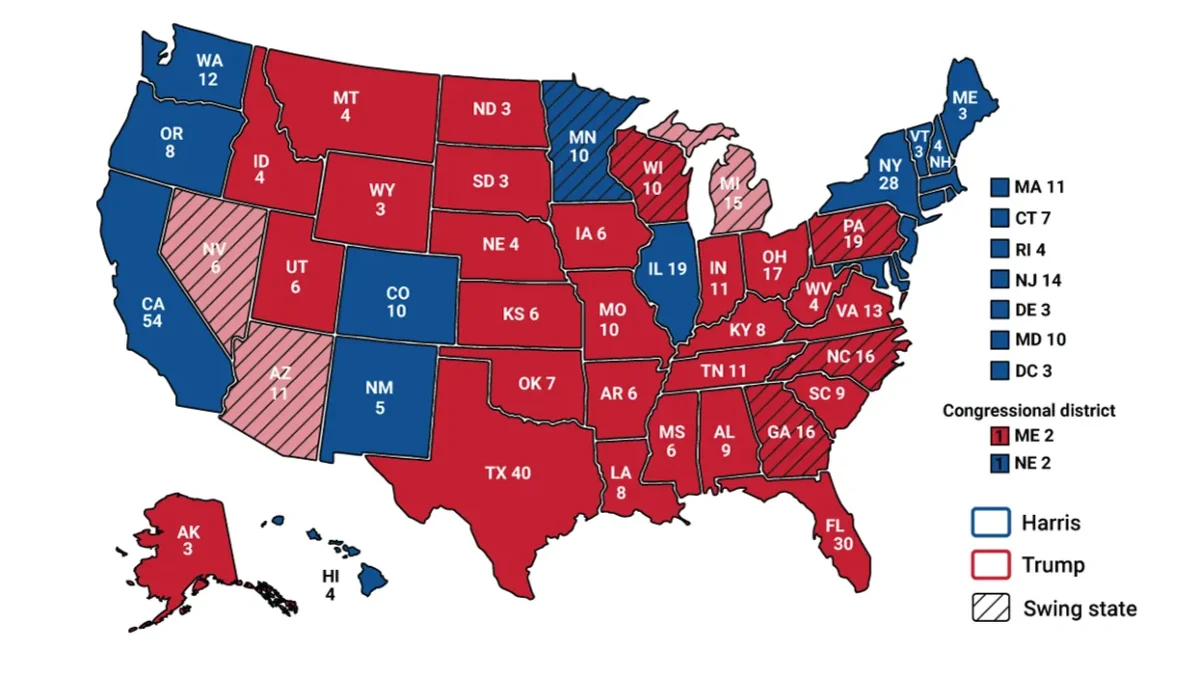

Recently, my father shared that my grandfather had encouraged him to major in international relations in India. He wanted my father to be a diplomat. I wish that I could talk to my grandfather about politics today, since I am considering majoring in that field or something similar.

I wish I had asked questions that prompted stories about his life. I wish I had not asked the same surface level questions (“How are you?”).

Most of all, I wish I had gotten to know him better while I could.