You can’t trust anyone,” said the girl, an anonymous senior at a local high school. The March 22 speaker session was approaching its end. The 30 or 35 parents and students gathered in the library were clearly exhausted from sitting and listening for two hours that evening, but they perked up at the new voice. The girl tried to look cheerful, yet as she spoke her face clearly showed the pain of her memories.

When the girl was a new student at her high school, a boy threatened to spread rumors about her if she did not “sext,” or send him a sexually explicit photo of herself by phone. She reluctantly complied and, within a day, the picture had spread through the whole school. Consequently, her reputation plummeted, and her fellow students began to physically and sexually harass her in the halls.

The worst part, though, involved the legal ramifications. She described how the police “treated her as the criminal” when they came to investigate the issue. They charged her with the creation of child pornography, which she avoided after fighting the charges in court. Even though the distribution and possession of child pornography are also felonies, the boy who spread the photo faced no legal charges.

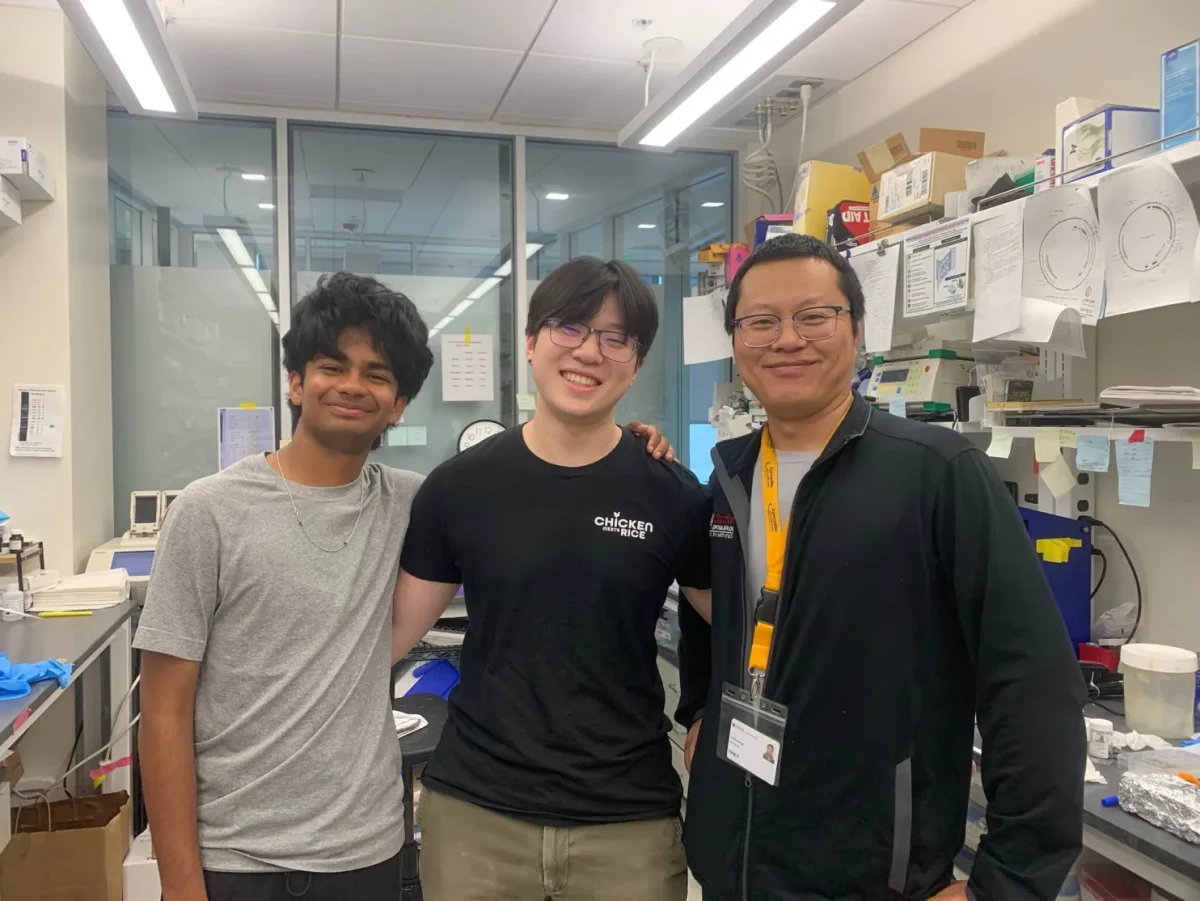

However, the main speaker of the night was licensed psychologist and social worker Tonja Krautter. A private practitioner in Los Gatos, Krautter has given workshops on topics ranging from eating disorders to rape crisis and trauma, including a training session on self-injury at Saratoga High.

Her talk in the library was called “Psychological, Physical and Legal Ramifications of Cyberbullying and Sexting on our Youth,” featuring the anonymous girl and her mother as visiting guest speakers near the end of the talk.

Krautter started off the two hours by introducing a trend in the underlying causes of “cyberbullying,” the harassment or humiliation of others through electronic means like texting, email or social media sites.

“People find a whole lot more courage when they are behind a screen,” Krautter said. “So even though the majority of people think [cyberbullying is] hysterical, it doesn’t always end that way for the people on the other end of it.”

She then gave some disturbing statistics: According to dosomething.org and isafe.org, 42 percent of children have been bullied online and 75 percent have visited websites where bullying is commonplace, but 58 percent of kids did not tell their parents when someone was abusive to them online. Krautter attributed the reluctance to talk about bullying mainly to children’s embarrassment and fear of vulnerability.

“A lot of kids think they can handle it,” she said.

Krautter highlighted the anonymous nature of cyberbullying. In traditional bullying, victims can either avoid their tormentors or confront them physically or verbally; however, cyberbullying victims often do not have those options.

“If you don’t know who your bully is, you can’t [use the traditional responses of] fight or flight,” Krautter said. “Cyberbullying can penetrate the walls of a home; there are no stay-home days from cyberbullying.”

She then showed a cyberbullying prevention commercial created by the National Crime Prevention Council. In the video, a young girl takes the stage of her school’s talent show only to slander one of her peers.

“The message of this commercial is if you’re not going to say it to someone’s face, don’t say it online,” Krautter said.

According to Krautter, the Internet’s weak moderation, easy accessibility and permanence catalyze cyberbullying. Websites rarely ban bullies or remove disparaging posts, leaving them online for anyone to see at any time.

She said that children should call out people for harassment, refuse to pass along hateful messages and report cyberbullying to adults. Parents, on the other hand, should educate their children about cyberbullying’s severe consequences.

Being the victim of bullying can lead to sleep disturbance, a sudden disinterest in school, somatic complaints (unexplained medical problems usually caused by stress), anxiety, depression, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a decrease in social activity and a new use of alcohol, tobacco or other drugs. Additionally, bullying victims often feel like they have run out of options and consider suicide.

Krautter offered two do’s and two don’ts for online safety.

“Don’t delete; always keep a record of the incident,” she said. “Don’t respond or seek revenge. It only escalates the problem, and then you can become a cyberbully too and face charges.”

She added, “Do tell—to get emotional support, to get the police involved if necessary—tell somebody, preferably an adult who can really help you. [Also,] do send an electronic message of encouragement and appreciation to someone who is not expecting it. That’s a really wonderful thing, to be able to give a gift to somebody who might be going through something like this.”

Krautter also mentioned the cyberbullying involved in sexting.

“There’s a lot of threatening and manipulation that go along with [sexting],” Krautter said. “People don’t realize how incredibly effective these online negative messages are in destroying someone.”

However, there is hope for the legal regulation and eventual elimination of cyberbullying, Krautter said. As of Jan. 1, 2009, California Assembly Bill 86 gives school administrators the authority to discipline for online bullying.

“A lot of times in the past administrators have said, ‘Well, [cyberbullying is] not my problem. It happens at home,’” Krautter said. “But it’s among the student body, so [the law] is a really big jump for California.”